In the autumn of 2021, geologists uncovered an odd row of stones nearly 1 kilometer long at the bottom of Mecklenburg Bay. The site is around ten kilometers off Rerik, with a sea depth of 21 meters. The nearly 1,500 stones are so precisely aligned that a natural origin is doubtful.

A team of scholars from many disciplines has recently established that Stone Age hunter-gatherers probably built this building around 11,000 years ago to hunt reindeer. This is the first discovery of a Stone Age hunting structure in the Baltic Sea region.

The scientists report their findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

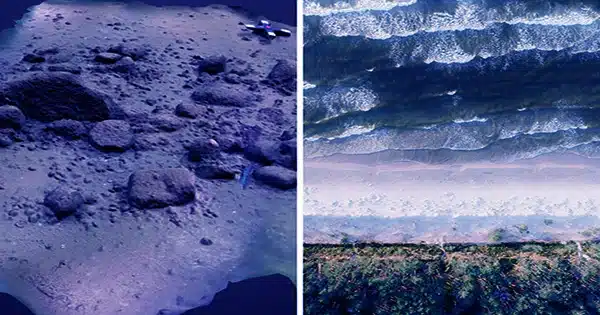

The discovery of the hunting site: Originally, a group of academics and students from Kiel University (CAU) sought to look at manganese crusts on a ridge of basal till that forms the seafloor about 10 kilometers off Rerik in Mecklenburg Bight. During their survey, however, they came across a 970-meter-long regular row of stones.

The structure is made up of approximately 1,500 stones, most of which are a few tens of centimeters in diameter and link many massive meter-scale rocks. The researchers reported their discovery to the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern State Agency for Culture and Monument Preservation (Landesamt für Kultur und Denkmalpflege Mecklenburg-Vorpommern LAKD M-V), which then coordinated additional investigations.

The stone wall is positioned on the southwestern slope of a ridge of basal till that runs nearly parallel to an adjacent basin in the south, which is likely a former lake or bog. Today, the Baltic Sea is 21 meters deep at this point. Thus, the stone wall must have been constructed before the water level rose dramatically following the end of the last ice age, which occurred approximately 8,500 years ago. Large portions of the previously accessible landscape were eventually submerged at that time.

Scientists from the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde (IOW), the CAU research focus Kiel Marine Science, the University of Rostock, the Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology (ZBSA, since 2024 part of the Leibniz Centre for Archaeology LEIZA), the German Aerospace Center (DLR), the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), and the LAKD M-V used modern geophysical methods to create a detailed 3D model. Using sediment samples from the adjacent basin to the south, it was possible to narrow down the time when the wall could have been constructed. Furthermore, research divers from the Universities of Rostock and Kiel investigated the stone wall.

“Our investigations show that both a natural origin for the underwater stone wall and recent construction, such as for undersea cable laying or stone harvesting, are unlikely. The planned placement of the many little stones that connect the massive, non-movable boulders contradicts this,” says Jacob Geersen, the study’s primary author. As part of the new IOW research emphasis “Shallow Water Processes and Transitions to the Baltic Scale,” Geersen is looking into geological and anthropogenic processes in the Baltic Sea.

Excluding natural processes and modern origins, the stone wall could only have been built after the last ice age, when the landscape had not yet been flooded by the Baltic Sea.

“At the period, the whole population of northern Europe was likely less than 5,000 individuals. Reindeer herds were one of their primary food sources, migrating periodically across the sparsely vegetated post-glacial environment. According to Marcel Bradtmöller of the University of Rostock, the wall was most likely designed to guide reindeer into a bottleneck between the surrounding lakeshore and the wall, or perhaps into the lake, where Stone Age hunters could easily kill them with their weapons.

Comparable prehistoric hunting structures have already been discovered in other parts of the world, such as about 30 meters below the surface of Lake Huron (Michigan). Archaeologists from the United States documented stone walls and hunting blinds built to hunt caribou, the North American equivalent of reindeer. The stone walls in Lake Huron and Mecklenburg Bight have several traits, including being located on the flank of a topographic ridge and having a subparallel trending lakeshore on one side.

Since the last reindeer herds vanished from our latitudes around 11,000 years ago, when the temperature warmed and woods spread, the stone wall was most likely not built after that.

This would make it the earliest human construction ever found in the Baltic Sea.

“Although numerous well-preserved Stone Age archaeological sites are known from the Bay of Wismar and along the coast of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, these are located in much shallower water depths and mostly date to the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods (approx. 7,000-2,500 BC),” explains Jens Auer from the Mecklenburg-Vorpommern State Office for Culture and Monument Preservation (LAKD M-V), who was involved in the exploration and sampling of many of these sites.

What’s next?

The stone wall and adjacent bottom will be thoroughly studied utilizing side-scan sonar, sediment echo sounders, and multibeam echo sounders. Furthermore, research divers from the University of Rostock and archaeologists from the LAKD M-V intend to conduct additional diving operations to investigate the stone wall and its surrounds for archaeological artifacts that could aid in the structure’s interpretation.

Luminescence dating, which may be used to establish when a stone’s surface was last exposed to sunlight, may aid in pinpointing the exact date the stone wall was built. Furthermore, the researchers plan to rebuild the old surrounding terrain in greater detail.

“We have evidence that similar stone walls exist elsewhere in the Mecklenburg Bight. “These will also be systematically investigated,” says Jens Schneider von Deimling of Kiel University.

Overall, the investigations have the potential to significantly contribute to our understanding of early Stone Age hunter-gatherers’ lives, organizations, and hunting strategies.