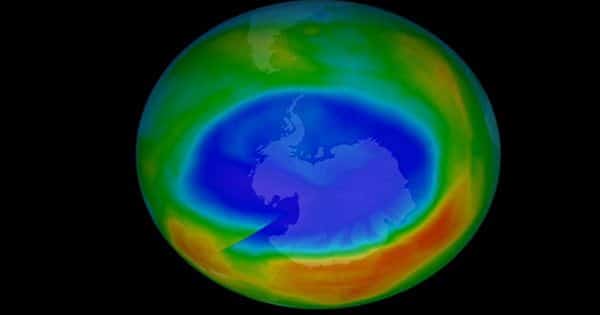

The unusually large hole in ozone levels across the Arctic last year was probably caused by a series of events caused by record high sea surface temperatures in the North Pacific Ocean, according to a new study published in Advances in Atmospheric Science. When you hear about holes in the ozone layer, it probably refers to a patch located above Antarctica in the Southern Hemisphere during the Austral spring around September, October and November each year.

The Arctic in the Northern Hemisphere is usually very warm for polar stratospheric clouds, which are the main drivers of the ozone depletion process in the spring. In the spring of 2020, however, an unprecedented hole was created over the Arctic. Scientists at the Chinese Academy of Sciences have now used satellite data and simulations to show that the hole was the result of record-high North Pacific surface temperatures occurring between February and March.

This warm sea surface temperature helps to weaken an important planetary wave (which helps to transfer heat from the tropics to the poles and maintain cold atmospheric balance from the poles to the tropics), affecting the Aleutian low, a large atmospheric low-pressure center that Lives frequently on the Aleutian islands near the Gulf of Alaska every winter. The result of this knock-on effect was a very cold and persistent stratospheric polar vortex between February and April 2020, which allowed the formation of polar stratospheric clouds by breaking the ozone layer.

The ozone layer is a region of the stratosphere 15 to 30 kilometers (9.3 to 18.6 miles) above the Earth’s surface where the gas has a high concentration of ozone. The layer absorbs a lot of the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays, which act as an invisible shield for our planet. This layer is degraded by chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) man-made chemicals that were once widely used as aerosol sprays, solvents, and refrigerants after floating in the stratosphere.

Although CFCs were phased out under the Montreal Protocol in the late 1980s, they remained hidden in the Earth’s atmosphere for some time. This is especially problematic when polar stratospheric clouds, high-altitude clouds are formed that help increase the chemical reactions associated with CFCs that lead to ozone depletion. The Montreal Protocol is rightly hailed as a remarkable achievement – to date it is the only UN environmental treaty ratified by every country in the world, and the ozone layer has improved significantly over the past three decades.