A new study connects an amphibian extinction in Costa Rica and Panama to an increase in malaria cases. The study emphasizes the significance of biodiversity to human health. Hundreds of frogs, salamanders, and other amphibians vanished from parts of Latin America between the 1980s and 2000s, with little notice from humans other than a small group of ecologists. Nonetheless, a study from the University of California, Davis found that the decline of amphibians had direct health consequences for people.

The study, published in the journal Environmental Research Letters, connects an amphibian extinction in Costa Rica and Panama to an increase in malaria cases in the region. At the spike’s peak, up to 1 person per 1,000 annually contracted malaria that normally would not have had the amphibian die-off not occurred, the study found.

“Stable ecosystems underpin all sorts of aspects of human wellbeing, including regulating processes important for disease prevention and health,” said lead author Michael Springborn, a professor in the UC Davis Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy. “If we allow massive ecosystem disruptions to happen, it can substantially impact human health in ways that are difficult to predict ahead of time and hard to control once they’re underway.”

Stable ecosystems underpin all sorts of aspects of human wellbeing, including regulating processes important for disease prevention and health. If we allow massive ecosystem disruptions to happen, it can substantially impact human health in ways that are difficult to predict ahead of time and hard to control once they’re underway.

Prof. Michael Springborn

A natural experiment

From the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, a deadly fungal pathogen known as Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis, or “Bd,” ravaged amphibian populations throughout Costa Rica. Through the 2000s, the amphibian chytrid fungus spread eastward across Panama. Globally, the pathogen was responsible for the extinction of at least 90 amphibian species, as well as the decline of at least 500 more.

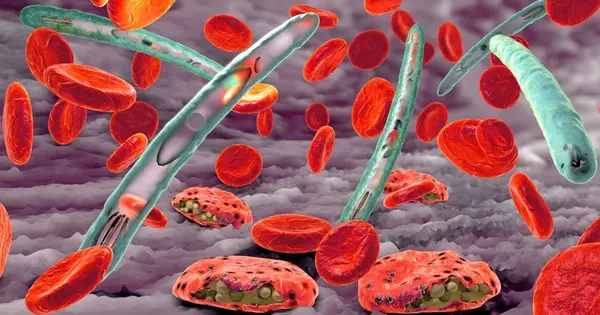

Both Costa Rica and Panama experienced an increase in malaria cases shortly after the mass extinction of amphibians. Each day, frogs, salamanders, and other amphibians consume hundreds of mosquito eggs. Malaria is spread by mosquitos. Scientists wondered if the decline in amphibians had anything to do with the rise in malaria cases.

To find out, the researchers combined their knowledge of amphibian ecology, newly digitized public health record data, and data analysis methods developed by economists to leverage this natural experiment.

“We’ve known for a while that complex interactions exist between ecosystems and human health, but measuring these interactions is still incredibly hard,” said co-author Joakim Weill, a Ph.D. candidate at UC Davis when the study was conducted. “We got there by merging tools and data that don’t usually go together. I didn’t know what herpetologists studied before collaborating with one!”

The findings show a clear relationship between the time and location of the spread of the fungal pathogen and the time and location of increases in malaria cases. While the researchers cannot completely rule out the possibility of another confounding factor, they found no evidence of other variables that could both drive malaria and follow the same pattern of die-offs.

The loss of tree cover was also associated with an increase in malaria cases, though not to the same extent as the loss of amphibians. Typical levels of tree canopy loss increase annual malaria cases by up to 0.12 cases per 1,000 people, compared to 1 in 1,000 for the amphibian die-off.

Trade threats

Concerns about the spread of similar diseases through international wildlife trade prompted the researchers to conduct the study. Batrachochytrieum salamandrivorans, or “Bsal,” for example, poses a similar threat to ecosystems via global trade markets.

Springborn stated that updating trade regulations to better target species that host such diseases as our knowledge of threats evolves could help prevent the spread of pathogens to wildlife.

“The costs of implementing those protective measures are immediate and obvious, but the long-term benefits of avoiding ecosystem disruptions like this one are more difficult to assess but potentially massive, as this paper demonstrates,” Springborn said.