Wastewater testing is a low-cost method for Latin American and Caribbean countries to improve their detection, diagnosis, control, and monitoring systems for viruses that cause diseases such as COVID-19 and its variants. According to a new World Bank report, this tool, which supplements clinical studies, provides public policymakers with a comprehensive, sustainable, early warning, and equitable tool for improving public health responses.

Through the Healthy Davis Together program, researchers have been monitoring wastewater on the UC Davis campus and in the city of Davis for COVID-19. A new article examines their experiences, as well as the benefits and drawbacks of wastewater testing as a public health tool in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since September 2020, researchers at the University of California, Davis have been monitoring wastewater on the UC Davis campus and throughout the city of Davis for COVID-19 as part of the Healthy Davis Together program. A new article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on February 8th reviews their experiences, as well as the benefits and limitations of wastewater testing as a public health tool in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Continued deployment of wastewater-based epidemiology in ways that take into account the needs of decision makers and pragmatically weigh costs and benefits will no doubt contribute significantly to the end of the pandemic.

Heather Bischel

The city/campus wastewater monitoring program is managed by Assistant Professor Heather Bischel and doctoral student Hannah Safford from the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, as well as Karen Shapiro, associate professor in the School of Veterinary Medicine. It now includes weekly, triweekly, or daily collections from over 50 sites spread across the UC Davis campus and city of Davis sewer networks. Their findings have aided in the return of students to campus and have assisted officials in understanding the spread of COVID-19 in the community.

“Continued deployment of wastewater-based epidemiology in ways that take into account the needs of decision makers and pragmatically weigh costs and benefits will no doubt contribute significantly to the end of the pandemic,” they wrote.

According to the report ‘Strengthening public health surveillance through wastewater testing: an essential investment for the COVID-19 pandemic and future health threats,’ investments in wastewater monitoring systems can yield long-term benefits by strengthening countries’ capacity to respond to public health threats in a timely and informed manner. As a result, best practices for measurement and report generation, as well as collaboration and coordination between health entities, laboratories, and services involved in wastewater collection, must be developed. This will necessitate an infrastructure that allows for a more extensive, well-organized, and long-term surveillance system.

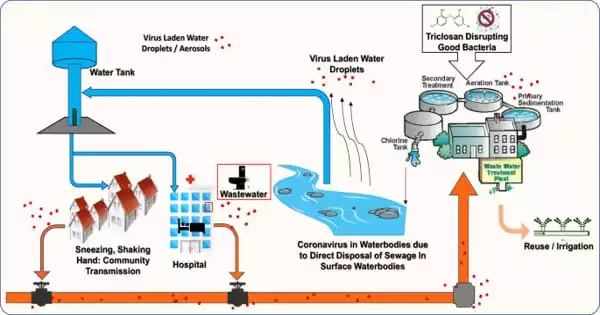

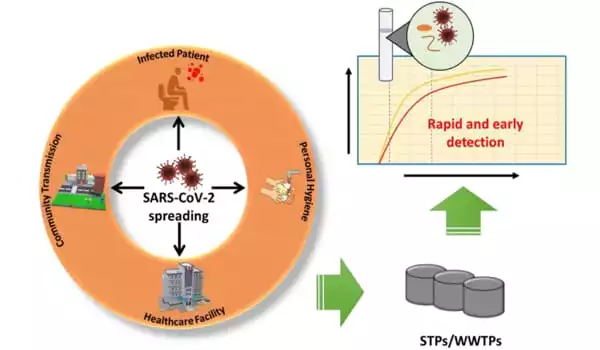

Rapid progress in the development of sewage monitoring for SARS-CoV-2 has the potential to contribute to public health action, such as early detection of secondary outbreaks. Many research and commercial labs have now gained valuable experience in the handling of sewage samples and virus analysis. However, there are still issues regarding how to use the results to advise health authorities, sample handling, and analytical techniques.

Advantages and limitations

Because infected people begin excreting virus days before developing symptoms, wastewater monitoring can provide a community-wide early warning of infection. When it comes to gathering data on disease levels in a region, the approach is also more cost-effective than large-scale individual clinical testing.

However, as Safford, Shapiro, and Bischel pointed out, wastewater monitoring has limitations. When community transmission is high, it is less effective as an early-warning system. Furthermore, while relatively inexpensive, wastewater monitoring is not free. To collect, process, and analyze samples, specialized equipment such as autosamplers are required, as well as personnel. Investing in wastewater monitoring can also take time and resources away from other projects.

Finally, deciding how to act on wastewater data can be difficult because the results do not reveal who may be infected: they can only point to a neighborhood or a building complex (such as a university dorm) that may be of concern. When local virus levels are on the rise, Healthy Davis Together uses wastewater data to strategically target email, text alerts, and incentives to encourage Davis residents to get tested.

Aside from the current pandemic crisis, wastewater testing can provide a snapshot of community health by analyzing a variety of pathogens present in wastewater. Its use enables more timely and comprehensive public health responses to diseases such as hepatitis A and influenza, as well as other community health risks such as antimicrobial resistance, chemical drug abuse, and pesticide overuse.

The PNAS article contains a number of recommendations for using wastewater monitoring in COVID-19 response. These include avoiding clinical testing redundancy, designing thoughtful sampling and data-analysis plans, defining action thresholds, monitoring fewer sites but more frequently, leveraging existing infrastructure, and being ready to adapt and communicate with other practitioners, epidemiologists, and public health officials.