When we think of Jurassic Park, the first things that come to mind are John Hammond’s amber stuff and the valuable “dino DNA” that comes out of the mosquito. In reality, amber specimens unfortunately / fortunately (depending on your perception of giant top predators) did not allow our dinosaurs to reproduce, but animals trapped in natural archives have given new insights into ancient ecosystems.

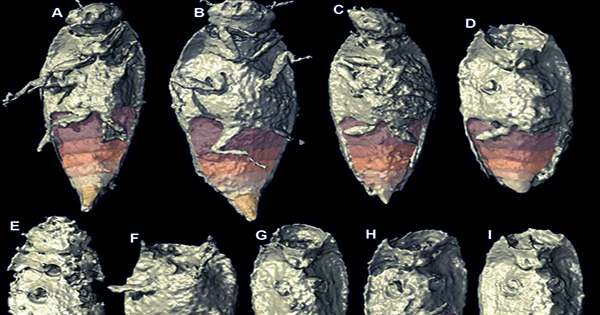

Just recently, a 50-million-year-old piece of amber revealed a fungus of an unknown genus and species that came out of the anus of an ancient carpenter’s ant. Science has now discovered a new species of beetle only the archive was a little less … glamorous. A new study published in the Journal of Current Biology has described a new-to-science beetle species found in the fossils of dinosaur ancestors. Also known as copolite, the foul-smelling cocoon freezes the beetles in a timely manner, preserves them in a 3D structure, and some even remain intact with their fine legs and antennae.

This dung is believed to have been deposited by a species from the Triassic period about 230 million years ago. This is a big pile of academic insights. The team in the new study used synchrotron microtomography to monitor the inside of the copolytes, an imaging technique they were already familiar with, in a 2017 study paper discussing its benefits for studying copolytes. “We kept an eye on the thinner parts of the copolite and realized that there was still a lot of fun food in them that we saved,” Martin Kavernstrom, an archaeologist at Uppsala University in Sweden, told IFLScience.

The new scientific beetle species has been named Trimyxa coprolithica, and it was speculated that the samples were probably so well preserved for the initial mineralization provided by the calcium phosphatic composition of the coprolite and the bacteria in the pupae. So, how did some near complete insects first get stuck inside a tard? Old-fashioned way, says Qvarnström. “These were probably invested. The reason why we believe this is that most beetle remnants are simply represented by isolated bits and pieces. A few samples are pretty close.