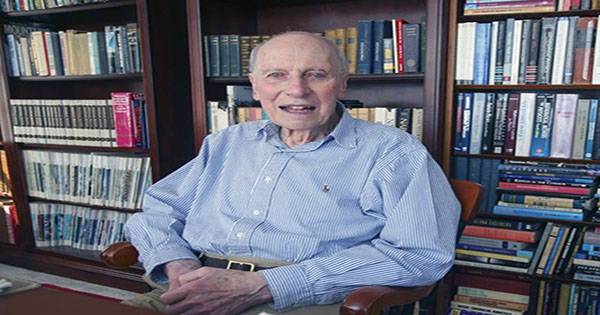

Dr. Manfred Steiner received his in Physics last month, fulfilling a lifelong ambition. That is a remarkable accomplishment in and of it, but it’s much more astonishing when you consider Steiner’s age of 89. In a statement, Steiner, who taught and then studied at Brown University, said, “It’s an ancient ambition that originates in my boyhood.” “I’ve always aspired to be a scientist.” By the time I finished high school, I knew physics was my true calling. My uncle and mother, however, recommended me to study medicine after the war since it would be a better decision in these uncertain postwar years.”

Dr. Steiner, who was born in Vienna, had a successful medical career, earning both an MD and a. Steiner’s interest in physics never wavered during his stellar medical career, and after he retired in 2000, he began to attend undergraduate lectures, first at MIT and then at Brown University, where he registered as a special student.

Steiner did not intend to pursue a third master’s degree. He hoped to take one or two classes every semester to keep his mind sharp, but by 2007, he had finished all of the requirements for graduate school and was accepted into the program.

When he was looking for a dissertation supervisor, he approached condensed matter theorist Brad Marston, who said that he was first hesitant to accept a septuagenarian as a student.

“To be honest, I was suspicious since most individuals do not take physics, especially theoretical physics until they are far into their senior years.” “Marston said.”In a moment of weakness, though, I consented and said “yes.” I was familiar with his tale and sympathized with his desire to pursue his lifetime ambition of being a physicist.”

When it came to Steiner’s subject, however, Marston did not treat him with child gloves. He tasked Steiner with dealing with the thorny problem of Bosonization. Based on a quantum feature called spin, the basic particles of the cosmos may separate into two major groups. There are fermions like quarks, electrons, and neutrinos, as well as bosons like photons, gluons, and the well-known Higgs boson. Bosonization, which is normally done as a one-dimensional problem allows you to treat a fermion as a boson in some uncommon conditions, Marston and his late colleague Tony Houghton devised two- and three-dimensional simulations to examine the situation. They ran into roadblocks in their approach, and it was up to Steiner and his to figure out how to get through them.

Steiner and Marston are currently working on publishing a portion of his dissertation findings, and Steiner will soon become one of the first published physicists. “I feel like I’m on top of the world right now,” Steiner remarked. “I hold this Ph.D. in the highest regard because it is the one for which I have worked my entire life.”