COVID-19 symptoms can last for months at a time. The virus can cause long-term health problems by causing damage to the lungs, heart, and brain. The majority of persons suffering with coronavirus illness 2019 (COVID-19) recover entirely within a few weeks. However, some people, even those with minor cases of the condition, continue to have symptoms after they have recovered.

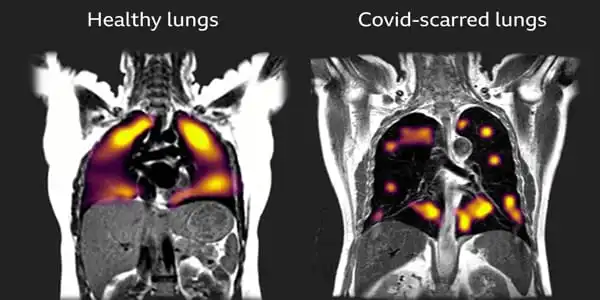

According to a paper published in eLife, scientists discovered that persistent inflammation following COVID-19 is highly connected to long-term alterations in lung structure and function. The findings imply that monitoring people for inflammatory markers following SARS-CoV-2 infection could aid in identifying those at risk of long-term lung issues and optimizing follow-up therapy.

Although the vast majority of COVID-19 patients have minor disease, a considerable proportion have persistent or recurring clinical symptoms, and full recovery can take months to years.

“Symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks are found in up to 10% of COVID-19 patients, and robust, resource-saving tools assessing people’s individual risk of lung complications are desperately needed,” says Thomas Sonnweber, a lung specialist at the Medical University of Innsbruck, Austria, and co-first author of the study with Piotr Tymoszuk. “We investigated if there are clinical hallmarks that can predict their likelihood of developing protracted COVID by analyzing the frequency of lung structure and function alterations and persistent symptoms in individuals six months after a COVID-19 diagnosis.”

We found a high frequency of structural and functional lung abnormalities and persistent symptoms six months after a COVID-19 diagnosis in our study group of patients, as well as a recovery trajectory that slowed after three months.

Judith Löffler-Ragg

The researchers assessed the recovery of 145 predominantly hospitalized COVID-19 patients who took part in the Austrian clinical study titled ‘Development of Interstitial Lung Disease in COVID-19’ between March and June 2020. (CovILD).

They analyzed patient characteristics during their acute COVID-19 infection and subsequently conducted follow-up studies at 60, 100, and 180 days. They used a questionnaire to assess symptoms and physical performance at each visit, and they also performed lung function tests, blood tests, and a chest scan.

Six months following diagnosis, over half of patients (49%) had persistent complaints, with the most prevalent being decreased physical performance (34.7 percent of patients), sleep difficulties (27.1 percent), and dyspnea on exercise (22.8 percent ). Although the frequency of these symptoms decreased over time, they were longer to resolve at the 100-day and 180-day follow-up visits, near the conclusion of the convalescence period.

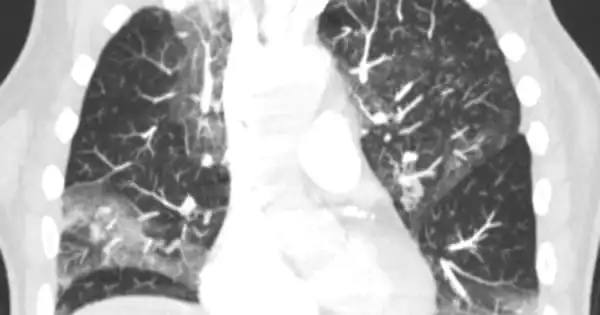

Six months following diagnosis, one-third of patients (33.6%) had decreased lung function, and nearly half of patients (48.5%) had chest scans demonstrating structural lung abnormalities, with one in every five patients (19.4%) having moderate-to-severe lung alterations.

The team employed machine learning algorithms to look for patterns of clinical features in individuals with chronic COVID symptoms in order to uncover risk variables related with these long-term difficulties. They discovered that risk factors associated with severe and critical COVID-19 infection, such as being male, having long-term conditions including high blood pressure, and having high anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels, were also associated with long-term symptom persistence. However, in addition to these characteristics, higher indicators of inflammation – both systemically and inside blood vessels – were linked to long-term lung problems.

The researchers subsequently investigated whether algorithms based on these risk factors might predict COVID outcomes in a separate set of patients. They discovered that, whereas inflammation indicators could predict who would have lung structure abnormalities, they could not identify who would suffer lung function difficulties or other symptoms such as shortness of breath. This shows that even if patients have measurable abnormalities in their lungs 60 days after diagnosis, these changes may not appear as symptoms or impairments in lung function right away, but could lead to issues later.

Before the algorithms can be used to predict long-term COVID-19 outcomes, they must be verified in larger groups of patients with COVID-19. To that purpose, the authors have made their findings available as an open-source risk assessment tool for use by other researchers.

“We found a high frequency of structural and functional lung abnormalities and persistent symptoms six months after a COVID-19 diagnosis in our study group of patients, as well as a recovery trajectory that slowed after three months,” says Judith Löffler-Ragg, a lung specialist at the Medical University of Innsbruck and co-senior author of the study with Ivan Tancevski. “Our risk models indicated a collection of clinical parameters associated with a longer recovery time, independent of infection severity, which included established inflammatory markers. We anticipate that these will be utilized to identify those who are at risk of developing chronic lung disease and optimize their care to prevent long-term handicap.”