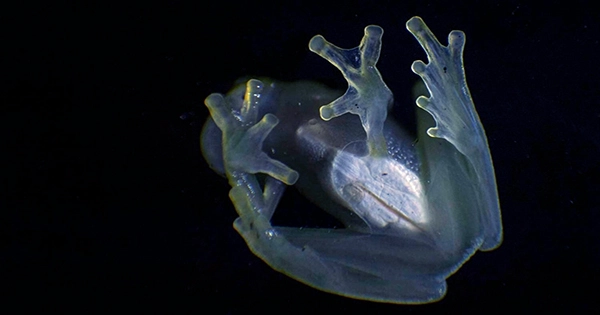

Glassfrogs have reflecting livers that enable them to store almost all of their red blood cells and conduct their distinctive “disappearing act,” which is how they are able to achieve transparency. Researchers from the American Museum of Natural History and Duke University recently released a paper in the journal Science that shed new insight on this unusual adaption and its possible effects on scientific research.

The American tropics are home to nocturnal amphibians called glassfrogs. Their transparent undersides and muscles, which allow their bones and internal organs to be seen through their skin, are what give them away. The frogs use this transparency as a kind of camouflage when they sleep upside down on transparent leaves during the day to fit in with their surroundings.

Since vertebrates struggle to acquire transparency due to the presence of red blood cells in their circulatory systems, which disrupt transparency and absorb light, transparency is a relatively uncommon adaption among land creatures. Glassfrogs, on the other hand, have discovered a different tactic that enables them to get around this obstacle.

The latest study shows that glassfrogs can double or triple their transparency by storing about 90% of their red blood cells in their livers, which contain reflective guanine crystals. Despite the fact that aggregating red blood cells in this fashion can frequently result in hazardous blood clots in veins and arteries in most vertebrates, the frogs are able to do this without having blood clots or other difficulties. This allows them to “hide” the red blood cells from view.

The researchers employed photoacoustic imaging, which stimulates sound waves in red blood cells, to investigate this process. As a result, they were able to map the location of the cells inside the frogs without the use of restraints, contrast materials, or surgical intervention. It was crucial to employ this procedure since activity, tension, anesthesia, and death all interfere with the glassfrogs’ transparency.

These frogs are able to “stop” their respiratory system throughout the day, even in hot weather, in order to store their red blood cells in their livers, according to the study’s focus on one particular species of glassfrog, the Hyalinobatrachium fleischmanni. They put the red blood cells back into circulation when they need to be active again, which enables them to move and lose their transparency.

Hopefully, these findings “will encourage the scientific effort to convert these frogs’ extraordinary physiology into fresh targets for human health and medicine,” according to Jesse Delia, the study’s co-lead author. The capacity of glass frogs to store and retrieve their red blood cells without developing blood clots poses important questions for biologists and physicians, and this finding may open up new research directions for the study of blood clots and other medical disorders.

Maomao Chen, Chenshuo Ma, Xiaorui Peng, Xiaoyi Zhu, Tri Vu, Junjie Yao, and Sönke Johnsen from Duke University, as well as Laiming Jiang, Qifa Zhou, and Lauren O’Connell from Stanford University, are additional authors on the paper. The National Science Foundation, the Human Frontier Science Program postdoctoral grant, and the National Geographic Society all provided funding for the project.