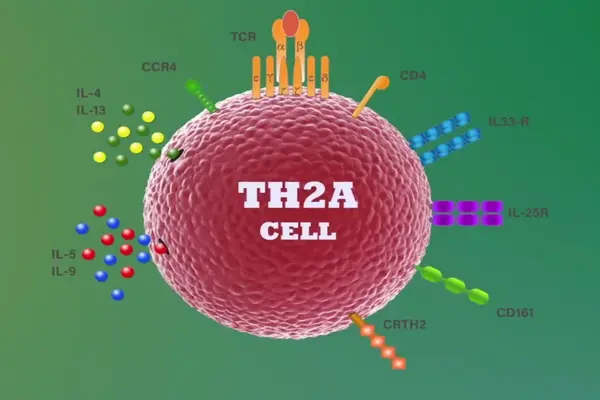

Researchers at McMaster University and the Danish pharmaceutical company ALK-Abello A/S have discovered a remarkable discovery: a novel cell that recalls allergies. The discovery provides scientists and researchers with a new target for treating allergies, potentially leading to new therapies. The study, published in Science Translational Medicine on February 7, 2024, refers to the new cell as a type-2 memory B cell (MBC2).

“We discovered a type of memory B cell with unique characteristics and a unique gene signature that has never been described before,” says Josh Koenig, an assistant professor in McMaster’s Department of Medicine and the study’s co-leader. “We found allergic people had this memory B cell against their allergen, but non-allergic people had very few, if any.”

B cells are a type of immune cell that makes antibodies. These cells help fight off infections but can also cause allergies.

We discovered a type of memory B cell with unique characteristics and a unique gene signature that has never been described before. We found allergic people had this memory B cell against their allergen, but non-allergic people had very few, if any.

Josh Koenig

“Let’s say you’re allergic to peanuts. Your immune system, because of MBC2, remembers that you’re allergic to peanuts, and when you encounter them again, it creates more of the antibodies that make you allergic,” Koenig says.

To make this discovery, researchers generated tetramers (a sort of fluorescent molecule) from allergens such as birch pollen and peanuts in order to locate difficult-to-find memory B cells. Koenig and his team have already written a guidebook on how to employ tetramers to find these elusive cells.

Researchers combined samples from ALK clinical trials with tablet sublingual immunotherapy, which enables for large-scale sequencing of IgE-producing B cells. Using cutting-edge technology such as single cell transcriptomics and deep sequencing of antibody gene repertoires on clinical trial samples, scientists were able to establish direct links between MBC2 and IgE, the kind of antibody that causes the allergic reaction. This provided the essential context, eventually showing the MBC2 as the source of allergy.

“Even though allergies are the most prevalent disease worldwide, it is still not fully understood how allergy occurs and evolves into a life-long condition. Finding the cells that hold IgE memory is a key step forward and a game-changer in our understanding of what causes allergy and how treatment, such as allergy immunotherapy, can modify the disease,” says Peter Sejer Andersen, senior vice-president and head of research at ALK. Sejer Andersen co-led the study with Koenig.

The discovery of MBC2 gives scientists and researchers a new target in treating allergies and could lead to new therapeutics.

“The discovery really pinpoints two potential therapeutic approaches we might be able to take,” says Kelly Bruton, who co-led the research alongside Koenig when she was a PhD student at McMaster. Bruton is now a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University.

“The initial step is to target and eliminate MBC2s from an allergic person. The other approach may be to change their function and have them do something that will not be damaging in the long run when the individual is exposed to the allergen.

More research will be needed to better understand and eventually develop therapies, but the finding of MBC2s provides new hope for those suffering from food allergies.

“These are the types of discoveries that you really need to make in order to develop the right therapeutics to block the right cells to stop the disease,” he says.