New research shows that the amygdala overgrows in the first year of life, before babies exhibit the majority of the behavioral characteristics that subsequently lead to a diagnosis of autism. Because babies with fragile X syndrome have a distinct brain maturation pattern, this overgrowth may be unique to autism.

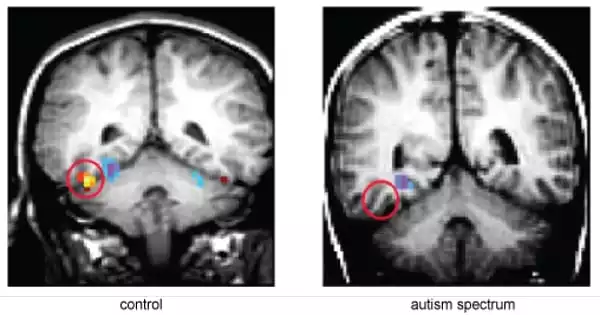

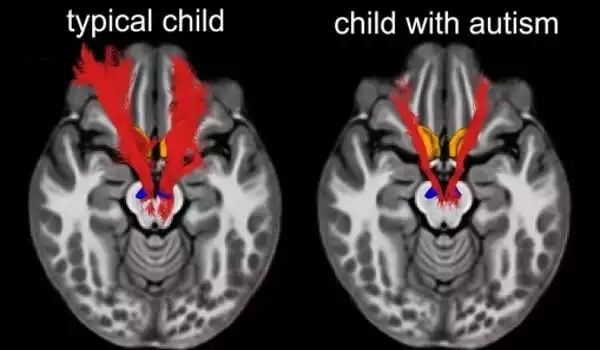

The amygdala is a tiny region deep in the brain that is vital for interpreting the social and emotional meaning of sensory input, such as identifying emotion in faces and deciphering frightened images that warn us of potential hazards in our surroundings. Historically, the amygdala was assumed to play a significant part in the social difficulties that are central to autism.

Researchers have known for a long time that the amygdala is abnormally large in school-age children with autism, but they didn’t know when that enlargement began. For the first time, researchers from the Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS) Network used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to show that the amygdala grows too quickly during childhood. Overgrowth begins between the ages of six and twelve months, prior to the age at which the hallmark symptoms of autism fully manifest, allowing for the earliest detection of this illness. The increased amygdala growth in newborns later diagnosed with autism differed significantly from brain-growing patterns in babies with another neurodevelopmental condition, fragile X syndrome, where no abnormalities in amygdala growth were identified.

According to our findings, the best time to start interventions and assist infants who are at high risk of developing autism is within their first year of life. A pre-symptomatic intervention could aim to improve visual and other sensory processing in neonates before social symptoms develop.

Joseph Piven

This study, which was published in the American Journal of Psychiatry, the official journal of the American Psychiatric Association, found that infants with fragile X syndrome already have cognitive delays at six months of age, whereas infants who will later be diagnosed with autism do not have any deficits in cognitive ability at six months of age, but have a gradual decline in cognitive ability between six and 24 months of age, the age when they were diagnosed with ASD.

Babies who go on to develop autism show no difference in the size of their amygdala at six months. However, their amygdala begins growing faster than other babies (including those with fragile X syndrome and those who do not develop autism), between six and 12 months of age, and is significantly enlarged by 12 months. This amygdala enlargement continues through 24 months, an age when behaviors are often sufficiently evident to warrant a diagnosis of autism.

“We also discovered that the rate of amygdala overgrowth in the first year is related to the child’s social deficits at age two,” said lead author Mark Shen, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Neuroscience at UNC Chapel Hill and faculty at the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities (CIDD). “The faster the amygdala expanded in infancy, the more social impairments the child displayed a year later when diagnosed with autism.”

This study, the first to show amygdala overgrowth before autism symptoms appear, was carried out by The Infant Brain Imaging Study (IBIS) Network, a collaboration of ten universities in the United States and Canada supported by a National Institutes of Health Autism Center of Excellence Network grant.

The researchers enrolled 408 infants, including 58 infants who were at increased risk of developing autism (due to having an older sibling with autism) and were later diagnosed with autism, 212 infants who were at increased risk of autism but did not develop autism, 109 typically developing controls, and 29 infants with fragile X syndrome. More than 1,000 MRI scans were taken during normal sleep at the ages of six, twelve, and twenty-four months.

So, what could be happening in these children’s brains to cause this overgrowth and, eventually, the development of autism? Scientists are beginning to put the puzzle pieces together.

Previous research by the IBIS team and others has demonstrated that, while the social deficits that characterize autism are not present at six months of age, infants who go on to develop autism have problems with how they attend to visual stimuli in their surroundings as neonates. The authors think that these early difficulties with processing visual and sensory information may exert additional stress on the amygdala, resulting to amygdala enlargement.

Amygdala overgrowth has been linked to chronic stress in studies of various psychiatric illnesses (e.g., depression and anxiety), and may provide a hint to explaining this phenomenon in children who acquire autism later in life.

Senior author Joseph Piven, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Departments of Psychiatry and Pediatrics, noted, “According to our findings, the best time to start interventions and assist infants who are at high risk of developing autism is within their first year of life. A pre-symptomatic intervention could aim to improve visual and other sensory processing in neonates before social symptoms develop.”