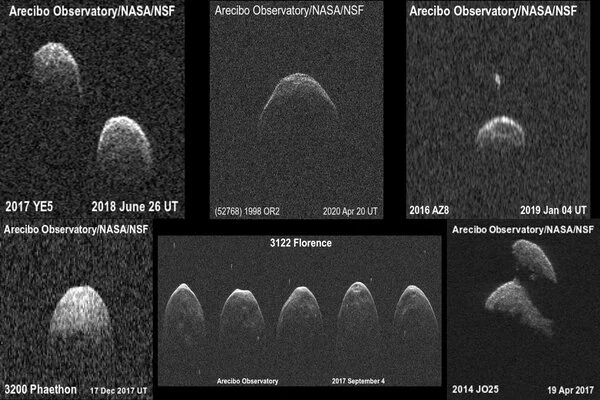

The specifications of an asteroid that made headlines in 2019 because it appeared out of nowhere and was moving quickly have just been published. When asteroid 2019 OK suddenly appeared barreling toward Earth on July 25, 2019, Luisa Fernanda Zambrano-Marin and the team at Puerto Rico’s Arecibo Observatory reacted quickly.

After receiving an alert, radar scientists focused on the asteroid, which was approaching from Earth’s blind spot — solar opposition. Zambrano-Marin and his colleagues had 30 minutes to collect as many radar readings as possible. She’d only have that much time in Arecibo’s sights because it was moving so quickly. Under a cooperative agreement, UCF manages the Arecibo Observatory for the National Science Foundation of the United States.

The asteroid made headlines because it appeared out of nowhere and was moving quickly. The findings of Zambrano-Marin were published in the Planetary Science Journal on June 10, just a few weeks before Asteroid Day, which is celebrated on June 30 and promotes global awareness to help educate the public about these potential threats.

“It was a real challenge,” says UCF planetary scientist Zambrano-Marin. “No one noticed it until it was practically passing by, so we had very little time to react when we received the alert. Nonetheless, we were able to gather a wealth of useful information.”

We can use new data from other observatories and compare it to the observations we have made here over the past 40 years. The radar data not only helps confirm information from optical observations, but it can help us identify physical and dynamical characteristics, which in turn could give us insights into appropriate deflection techniques if they were needed to protect the planet.

Zambrano-Marin

Turns out the asteroid was between .04 and .08 miles in diameter and was moving fast. It was rotating at 3 to 5 minutes. That means it is part of only 4.2 percent of the known fast rotating asteroids. This is a growing group that the researchers say need more attention.

According to the data, the asteroid is most likely a C-type, which is composed of clay and silicate rocks, or an S-type, which is composed of silicate and nickel-iron. C-type asteroids are some of the most common and oldest in our solar system. The second most common are S-types.

To continue her research, Zambrano-Marin is now inspecting the data collected by Arecibo’s Planetary Radar database. Despite the fact that the observatory’s telescope will be destroyed in 2020, the Planetary Radar team will be able to use the existing data bank, which spans four decades. Science operations in space and atmospheric sciences continue, and the staff is refurbishing 12-meter antennae to continue astronomy research.

“We can use new data from other observatories and compare it to the observations we have made here over the past 40 years,” Zambrano-Marin says. “The radar data not only helps confirm information from optical observations, but it can help us identify physical and dynamical characteristics, which in turn could give us insights into appropriate deflection techniques if they were needed to protect the planet.”

According to the Center for Near Earth Studies, there are nearly 30,000 known asteroids, and while few pose an immediate threat, there is a chance that one of significant size could strike the Earth and cause catastrophic damage. That is why NASA keeps a close eye on things and has a system in place to detect and characterize objects once they are discovered. NASA and other space agencies have launched missions to explore Near-Earth Asteroids in order to better understand what they are made of and how they move in the event that one of them collides with Earth in the future.

The OSIRIS REx mission, led by UCF Pegasus Professor of Physics Humberto Campins, is returning to Earth with a sample of asteroid Bennu that surprised scientists. Bennu was first discovered in 1999 at Arecibo. NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) mission aims to demonstrate the capability of redirecting an asteroid using projectile kinetic energy. The spacecraft will launch in November 2021 and will arrive at its destination, the Dimorphos asteroid, on September 26, 2022.

Zambrano-Marin and the rest of the Arecibo team are working to provide more information to the scientific community about the various types of asteroids in the solar system in order to help them develop contingency plans.

The team at the Arecibo Observatory is holding a series of special events as part of the Asteroid Day awareness campaign. They include presentations, “ask a scientist” stations for those visiting the science museum at Arecibo, and on June 25 presentations about the DART mission in English and Spanish. The timing couldn’t be better as there are five known asteroids from the size of a car to a Boeing 747 that will be buzzing Earth before Asteroid Day, according to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory that keeps track of the celestial bodies for NASA. The closest approach is on June 25 with an object coming within 475,000 miles of Earth. For comparison, the moon is about 239,000 miles from Earth.