According to a study published in the journal iScience, researchers generated induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) and cerebral organoids from the last male Malaysian Sumatran rhino. According to the authors, the organoids could help to understand the evolutionary progression of brain development in mammals and may help to uncover the rhinoceros family’s ancient history.

“To the best of our knowledge, cerebral organoids have only been obtained from mouse, human, and nonhuman primate pluripotent stem cells so far,” says senior study author Sebastian Diecke of the Helmholtz Association’s MaxDelbrückCenter for Molecular Medicine (MDC)

“We were ecstatic to see the formation of mini-brains from Sumatran rhino iPSCs in a manner that appeared to be comparable to that described for human organoids.”

The sixth mass extinction is moving at an unprecedented rate. The five extant rhinoceros species are particularly vulnerable due to poaching, habitat destruction, and fragmentation. The Sumatran rhino, also known as the hairy or Asian two-horned rhino, is the smallest and oldest rhinoceros species still alive. It is important in shaping forests and spreading the seeds of at least 79 different plant species.

To the best of our knowledge, cerebral organoids have only been obtained from mouse, human, and nonhuman primate pluripotent stem cells so far. We were ecstatic to see the formation of mini brains from Sumatran rhino iPSCs in a manner that appeared to be comparable to that described for human organoids.

Sebastian Diecke

There are only about 80 Sumatran rhinos left in the world. They used to live in a continuous, vast area in East and Southeast Asia. However, only small, fragmented populations remain scattered across Sumatra and Indonesian Borneo. The most serious threats to the species are habitat loss and limited breeding opportunities, which are causing a steady population decline.

To stop the erosion of genetic diversity, the reintroduction of genetic material is indispensable. Because the propagation rate of captive breeding is too low, innovative technologies need to be developed. iPSCs are a powerful tool to fight extinction. They give rise to each cell within the body, including gametes, and provide a unique approach to preserve genetic material across time. Beyond application in innovative conservation strategies, iPSCs from endangered species enable research on species-specific developmental processes.

In the new study, Diecke and his collaborators generated iPSCs from the last male Malaysian Sumatran rhino, Kertam, who died in 2019, and characterized them comprehensively. The iPSCs gave rise to cells of the three germ layers.

“We conserved his genetic information and created an opportunity to produce viable spermatozoa for breeding purposes in the future,” says first author Vera Zywitza of MDC. “As the quality of semen collected from Sumatran rhinos is poor directly after retrieval and even worse after cryopreservation and thawing, in vitro-generated spermatozoa offer a great alternative for assisted breeding of Sumatran rhinos in general.”

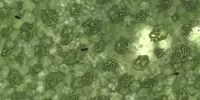

Furthermore, the cerebral organoids demonstrate iPSCs’ ability to generate complex 3D structures and represent a promising application for studying the evolution of brain development across species. The organoids were self-organized and expressed all of the neural markers tested. Taken together, this research represents the first step toward using stem-cell-associated techniques to combat the extinction of the Sumatran rhino.

“We hope that the general public gains an understanding of the tremendous potential of iPSCs and the wide range of applications for which they can be used,” Diecke says. “We also hope to raise awareness of the ongoing sixth mass extinction event, which is being caused by human activities, as well as the enormous efforts required to save a single species.”