The European colonization of the Americas is often portrayed as a rapid movement that spread uniformly across the continent, sharply dividing indigenous cultures by disease or violence. Even after the colonial barbarism remained perfectly clear, a new archaeological study has begun to rewrite the Euro-centric interpretation of the phenomenon. Archaeologists at the University of Washington in St. Louis have shown that indigenous peoples in the Oconee Valley in present-day Central Georgia have actively resisted and actively resisted European influence for over a century.

Jacob Lulewicz, lead study author and a lecturer in archaeology, said in a statement, “The case study presented in our research paper highlights the longevity and endurance of indigenous Mississippi traditions and references the historical context of the early colonial struggle in the Oconee Valley by rewriting conversations between Spanish colonists and Native Americans.”

The breakthrough comes from a sacred site in present-day Green County known as Dyar, once used by the Oconee Valley aborigines – the ancestors of the later Muscogee (Creek) tribes, reported in the journal American Antiquity.

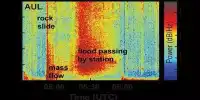

Researchers using advanced radiocarbon dating and mathematical modeling established the BBT as it was used in the late 1670s. Dating indicates that indigenous culture was practiced for 130 years after the first war between indigenous peoples and colonists in 1540 AD. There is no evidence of European culture on this site, in which the aborigines offered some resistance against the colonists. It is far from the previous theories that most of the indigenous sites in the region were abruptly abandoned after the first battle with the Spanish colonists.

Lulewicz added, “The ancestors of Muscogee (Creek) did not continue their traditions on Diyarbakir for nearly a century and a half after the conflict, they also actively rejected European issues.”

The team will hope to give a stronger voice to the indigenous peoples as well as talk about this unique chapter of history, as well as showcase the incredible endurance and strength of their culture, through this study. “Today there are no indigenous tribes in Georgia because they were all forcibly removed in the nineteenth century, so it is really important to make this clear link to those whose ancestors once lived across Georgia for thousands of years. Without this kind of work, we are contributing to the deprivation of indigenous peoples from history,” he said.

“Of course, they already knew a lot of the things we’ve discovered, but it still made sense to be able to reaffirm their ancestral connection to their land.” Dyar mound is far from a standalone example. Lulewicz and his team argued that there is evidence on many indigenous sites that they settled in the Fatherland site, Cofitachequi, South Carolina, and the Lower Mississippi Valley, still associated with Natchez, Louisiana, after the 16th century. However, scientific confirmation is still needed for some of these examples, he added.