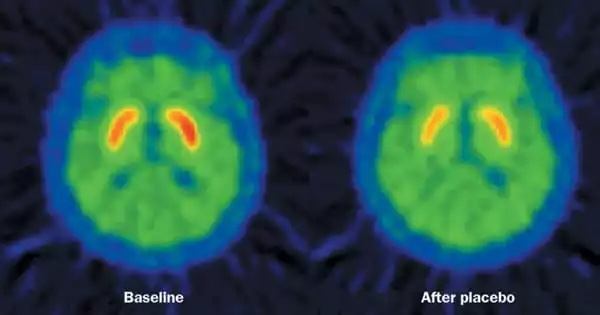

The placebo effect stimulates the same brain pathways that brain-stimulation therapy for depression does. According to a new study, a network of brain regions activated by the placebo effect overlaps with several regions targeted by brain-stimulation therapy for depression. The study was conducted by a team of researchers from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and colleagues from the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre at the University of Toronto.

The findings of this study, published in Molecular Psychiatry, may help researchers better understand the neurobiology of placebo effects and may influence how therapeutic trials of brain stimulation are interpreted. This research may potentially provide insights into how to use placebo effects to treat a number of illnesses.

The placebo effect happens when a patient’s symptoms improve because he or she anticipates a therapy to help (for a variety of reasons), but not because of the treatment’s specific benefits. Recent study reveals that the placebo effect has a neurological foundation, with imaging tests finding a pattern of changes that occur in certain brain regions when a person experiences this phenomena.

In recent years, the use of brain-stimulation treatments for patients with depression who do not react sufficiently to medicine or psychotherapy has grown in popularity. TMS is a non-invasive treatment in which a practitioner places a coil on the patient’s head and transmits electromagnetic pulses to the brain. TMS’s influence on brain activity has been confirmed in animal and human research studies over the last three decades, with numerous TMS devices approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating depression. Furthermore, there is an increasing body of research on the use of deep brain stimulation (DBS, which needs an implanted device) for difficult-to-treat depression.

We believe this is an important first step toward understanding the placebo effect in general, as well as learning how to modulate and harness it, including using it as a potential therapeutic tool by intentionally activating brain regions of the placebo network to elicit positive effects on symptoms.

Emiliano Santarnecchi

Emiliano Santarnecchi, PhD, senior author of the Molecular Psychiatry paper and director of the Precision Neuroscience & Neuromodulation Program at MGH’s Gordon Center for Medical Imaging, saw brain stimulation studies as a unique opportunity to learn more about the neurobiology of the placebo effect.

Santarnecchi and his colleagues performed a meta-analysis and review of neuroimaging studies including healthy and sick people to produce a “map” of brain regions activated by the placebo effect. They also examined trials of persons treated for depression with TMS and DBS to identify brain areas targeted by the therapies. The researchers discovered that multiple brain areas triggered by the placebo effect overlap with brain regions targeted by TMS and DBS.

Santarnecchi and his colleagues believe that this overlap is crucial in evaluating the findings of brain stimulation studies for illnesses such as depression. In clinical trials, a considerable proportion of depression patients who receive brain stimulation improve, but so do many patients who receive placebo (sham) treatment, which results in misunderstanding about the therapy’s advantages.

According to Santarnecchi, one probable explanation is “that there is a huge placebo effect when you conduct any type of brain stimulation intervention.” Unlike taking a pill, TMS treatment is administered in a surgery-like setting, with imaging monitors and a physician attaching a coil to the patient’s head. With each pulse, there are loud clicks. “So the patient thinks, ‘Wow, they’re really stimulating my brain,’ and you have a lot of expectation,” Santarnecchi explains.

According to the first author of the report, cognitive neurologist Matthew Burke, MD, of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, elevated placebo effects linked with brain stimulation may cause issues when investigating the intervention. If brain stimulation and the placebo effect both activate the same brain regions, then those circuits may be maximally activated by placebo effects, making it difficult to demonstrate any additional benefit from TMS or DBS, according to Burke.

If that’s the case, this study could explain why clinical studies of neurostimulation for depression and other disorders have yielded such mixed outcomes. Separating the placebo component of brain stimulation therapies from their actual effects on brain activity would aid in the design of research in which the true potential of techniques like as TMS can be more easily quantified, hence enhancing the efficacy of treatment procedures.

According to Santarnecchi, the outcomes of this study imply that the placebo effect has a wide range of uses. “We believe this is an important first step toward understanding the placebo effect in general, as well as learning how to modulate and harness it, including using it as a potential therapeutic tool by intentionally activating brain regions of the placebo network to elicit positive effects on symptoms,” he says. Santarnecchi and his colleagues are now designing experiments in the hopes of “disentangle[ing]” the effects of brain stimulation from placebo effects and providing insights into how they may be used in clinical settings.