According to new research from Georgia Tech’s School of Public Policy, the state of Georgia could dramatically reduce greenhouse gas emissions while creating new jobs and a healthier public if more of its energy-intensive industries and commercial buildings use combined heat and power (CHP).

The paper, which is now available digitally and will be published in print on December 15 in the journal Applied Energy, finds that CHP or cogeneration could significantly reduce Georgia’s carbon footprint while creating green jobs. According to data from the US Energy Information Administration, Georgia ranks eighth among all 50 states in total net electricity generation and eleventh in total carbon dioxide emissions.

“There is an enormous opportunity for CHP to save industries money and make them more competitive, while also reducing air pollution, creating jobs, and improving public health,” said principal investigator Marilyn Brown, Regents and Brook Byers Professor of Sustainable Systems at Georgia Tech’s School of Public Policy.

Benefiting the Environment, Economy, and Public Health

According to the study, if Georgia added CHP systems to the 9,374 sites that are suitable for cogeneration, it could reduce carbon emissions by 13%. Adding CHP to just 34 of Georgia’s industrial plants, each with 25 megawatts of electricity capacity, could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2%. The study’s authors note that this “achievable” level of CHP adoption could add 2,000 jobs to the state; full deployment could support 13,000 new jobs.

There is an enormous opportunity for CHP to save industries money and make them more competitive, while also reducing air pollution, creating jobs, and improving public health. It’s taken a long time, but there are finally more and more of these digester or biomass operations using CHP to generate electricity and thermal energy from waste resources.

Marilyn Brown

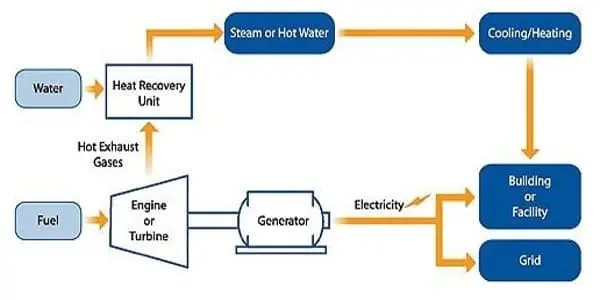

According to Brown, CHP systems can be 85 to 90 percent efficient, compared to traditional heat and power systems’ 45 to 60 percent efficiency. CHP has advantages over renewable energy sources such as solar and wind, which only provide intermittent power.

CHP technologies generate electricity that can be used for both heating and cooling, resulting in extremely high system efficiencies, cleaner air, and more affordable energy. Chemical, textile, pulp and paper, and food production are among the Georgia industries that would benefit from CHP. CHP could also benefit large commercial buildings, campuses, and military bases. The energy system is more reliable, resilient, and efficient because it uses both electricity and heat from a single source on-site.

Brown explained that CHP can meet the same needs more efficiently while using less overall energy and reducing peak demand on a region’s utility-operated power grid. Furthermore, if there is a power outage or disruption in a community’s power grid, businesses with their own onsite electricity sources can continue to operate.

Calculating CHP Costs and Benefits per Plant

The study used a database of every Georgia industrial site to determine which facilities had or could have a CHP system. They then identified the appropriate type of CHP system for plants that did not have one. To determine whether a CHP system was a financially sound investment, they created a model that estimated the benefits and costs of each CHP system, taking into account the cost of installation, operations and maintenance, fuel expenses, and financing. Brown explained that the result was an estimated “net present value” of each system that reflected the present value of future costs and benefits.

The paper also used data analytics to forecast the economic and health benefits of CHP for Georgians. Plants that convert to cogeneration could increase the state’s clean energy workforce by 2,000 to 13,000 jobs, depending on how widely it is adopted, according to Brown. According to the 11th Annual National Solar Jobs Census 2020, the state currently has about 2,600 jobs in electric vehicle manufacturing and less than 5,000 jobs in the solar industry.

Brown emphasized that, in addition to job growth, CHP adoption could result in significant health benefits for the state’s most vulnerable residents. “We’re displacing more polluting electricity when companies generate their own from waste heat,” she pointed out.

In the “achievable” scenario for CHP, the study estimates nearly $150 million in reduced health costs and ecological damages in 2030, with nearly $1 billion in health and environmental benefits if every Georgia plant identified in the study adopted CHP.

Drawdown Georgia, a statewide initiative focused on scaling market-ready, high-impact climate solutions in Georgia this decade, funded Georgia Tech’s research. The organization has identified a roadmap of 20 solutions, including CHP and other electricity solutions.

The impact of CHP could be dramatic, given that electricity generation accounts for nearly 37 percent of Georgia’s energy-related carbon dioxide emissions, according to findings published earlier this year in the journal Environmental Management by Brown and other researchers.

Identifying Ideal CHP Sites

Georgia Tech researchers identified a variety of industrial sites in Georgia that could benefit from combined heat and power. Established universities or military bases, as well as large industrial sites such as paper mills, chemical plants, and food processing plants, are ideal locations. Agriculture is Georgia’s leading industry, with chemicals and wood products among the state’s top manufacturers.

“I am very interested in Georgia’s potential to build CHP plants using existing industrial and commercial facilities,” said study co-author Valentina Sanmiguel, a 2020 master’s graduate of the School of Public Policy in sustainable energy and environmental management. “I hope that both industries and policymakers in Georgia recognize the benefits of cogeneration to the environment, economy, and society and take action to implement CHP on a larger scale in the state.”

Dissecting Hurdles to Adoption

Despite the benefits of CHP, there are still barriers to its widespread adoption. For example, establishing these facilities is capital-intensive, with costs ranging from tens of millions for a campus CHP plant to hundreds of millions for a large plant on an industrial site. Brown explained that once built, these facilities will require their own workforce to operate. “The cost-competitiveness of CHP systems is heavily dependent on two factors: whether they are customer-owned or utility-owned, and the type of rate tariff they operate under,” Brown explained.

Georgia Tech cites three ways to improve the business case for CHP in the paper: clean energy portfolio standards, regulatory reform, and financial incentives such as tax credits. He went on to say that North Carolina has a policy that encourages the use of renewable energy. In addition to solar and wind energy, North Carolina has embraced the conversion of waste from swine and poultry feeding operations into renewable energy.

“It’s taken a long time, but there are finally more and more of these digester or biomass operations using CHP to generate electricity and thermal energy from waste resources,” he said. While Georgia Tech does not yet have a CHP system, the Campus Sustainability Committee is looking into ways to reduce their energy footprint.

“Georgia Tech seeks to leverage Dr. Brown’s important research, as well as Georgia Tech’s deep faculty expertise in climate solutions, as we move forward with the development of a campus-wide Carbon Neutrality Plan and Campus Master Plan in 2022,” said Anne Rogers, associate director, Office of Campus Sustainability. “The Campus Master Plan and Carbon Neutrality Plan will serve as a road map for implementing sustainable infrastructure solutions that will help Georgia Tech achieve its strategic goals.”

Brown emphasized the importance of Georgia utilities supporting cogeneration projects in order to help the state reduce its carbon footprint. Another barrier is the Southeast’s relatively low electric rates, which provide less of an opportunity to achieve a reasonable payback on those systems. Georgia’s industries that want to be competitive globally should consider CHP because the rest of the world is embracing renewable and recycled energy at a faster rate than the United States, according to Brown.