Validity and Limitations of Henry’s Law

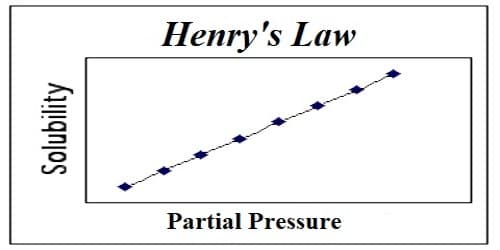

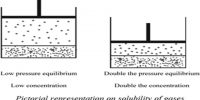

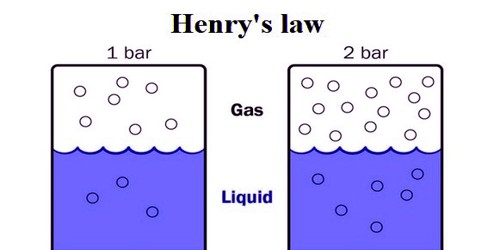

Henry’s law is obeyed fairly satisfactorily by many gases of low solubility, provided the pressure is not too high or the temperature is not too low. This is because Henry’s law is intimately connected with ideal gas law. Henry’s law states that: At a constant temperature, the amount of a given gas dissolved in a given type and volume of liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of that gas in equilibrium with that liquid. This law gives a correlation between the solubility of gas & its pressure. According to this law – “The mass of a gas dissolved per unit volume of the solvent at a given temperature is proportional to the pressure of the gas in equilibrium with the solution.”

Large deviations from Henry’s law are observed in the case of gases of high solubility and particularly those which interact with the solvent liquid, e.g., ammonia and hydrogen chloride gas in water. Ammonia forms ammonium hydroxide which partly dissociates into ammonium and hydroxyl ions while hydrogen chloride gas forms hydrogen and chloride ions in water.

This law is obeyed comparatively acceptably by many gases of low solubility, provided the pressure is not too high or the temperature is not too low. This is because Henry’s law is thoroughly associated with ideal gas law.

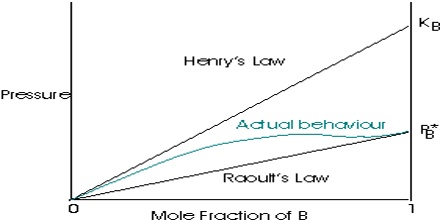

This law is only valid for low dissolved gas concentrations. Henry’s law is a limiting law that only applies to “sufficiently dilute” solutions. The range of concentrations in which it applies becomes narrower the more the system diverges from ideal behavior.

Large deviations from Henry’s law are observed in the case of gases of high solubility and mostly those which relate with the solvent liquid,

Limitations –

The law is exactingly appropriate to those gases where the molecular species are similar in the liquid phase. If proper corrections of the similar molecular species in the two phases are determined, Henry’s law might be appropriate. This indeed was found to be true in the case of ammonia.

The gases reacting with the solvent do not follow this law. For example, ammonia or HCl reacts with water and hence does not obey this law.

NH3 + H2O ⇆ NH4+ + OH–

The gases obeying Henry’s law should not connect or dissociate while dissolving in the solvent.

Deviations from this law in these cases are attributed to change in the molecular species as a result of dissolution. The law is strictly applicable to those gases where the molecular species are the same in the liquid phase. If suitable corrections are applied to account for such interactions, and concentrative of the same molecular species in the two phases are determined, Henry’s law might be applicable. This indeed was found to be true in the case of ammonia.

Henry’s law is appropriate only when –

- The pressure is not high. The pressure of the gas is not too high and warmth is not too low.

- Temperature is not too low; the gas should not experience connection or dissociation in the solution.

- The gas is not extremely soluble; the gas should not go through any chemical transform.

- The gases neither react chemically with solvent nor dissociate or connect in the solvent.