A new study provides the earliest evidence to date of ancient humans using flames to significantly alter entire ecosystems. The study combines archaeological evidence from dense clusters of stone artifacts dating back 92,000 years with paleoenvironmental data from the northern shores of Lake Malawi in eastern Africa to demonstrate that early humans were ecosystem engineers.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, combines archaeological evidence (dense clusters of stone artifacts dating back as far as 92,000 years) with paleoenvironmental data from the northern shores of Lake Malawi in eastern Africa to demonstrate that early humans were ecosystem engineers. They used fire in a way that prevented the region’s forests from regrowing, resulting in the sprawling bushland that exists today.

In this video, Yale paleoanthropologist Jessica Thompson describes the earliest evidence of humans altering their ecosystem with fire. “This is the earliest evidence I have seen of humans fundamentally transforming their ecosystem with fire,” said Jessica Thompson, the paper’s lead author and assistant professor of anthropology in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. “It suggests that by the Late Pleistocene, humans were discovering new ways to use fire. In this case, their burning resulted in the region’s forests being replaced by the open woodlands that exist today.”

Mastery of fire has given humans dominance over the natural world. A Yale-led study provides the earliest evidence to date of ancient humans significantly altering entire ecosystems with flames.

Thompson co-authored the study with 27 other researchers from the United States, Africa, Europe, Asia, and Australia. Thompson oversaw the archaeological work in collaboration with Malawi’s Department of Museums and Monuments; David Wright of the University of Oslo oversaw efforts to date the study’s archaeological sites, and Sarah Ivory of Penn State oversaw the paleoenvironmental analyses.

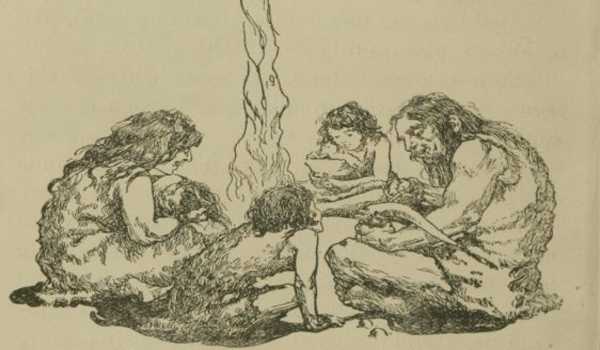

The researchers examined artifacts from Africa’s Middle Stone Age, which dates back at least 315,000 years. During this time, the earliest modern humans appeared, with the African archaeological record revealing significant advances in cognitive and social complexity.

Thompson and Wright worked in the region for several field seasons before a conversation with Ivory helped them make sense of the patterns they saw in their data. The researchers discovered that the regional archaeological record, ecological changes, and the development of alluvial fans near Lake Malawi – an accumulation of sediment eroded from the region’s highland – all dated to the same time period, implying that they were linked.

The water level in Lake Malawi has fluctuated dramatically over time. The lake was reduced to two small, saline bodies of water during its driest periods, the most recent of which ended about 85,000 years ago. According to the study, the lake recovered from these arid stretches and its levels have remained high ever since.

The archaeological data were gathered from over 100 pits excavated across hundreds of kilometers of the alluvial fan that formed during this period of stable lake levels. The paleoenvironmental data are based on pollen and charcoal counts that settled to the lakebed and were recovered later in a long sediment core drilled from a modified barge.

The data revealed, according to the researchers, that a spike in charcoal accumulation occurred shortly before the region’s species richness (the number of distinct species inhabiting it) flattened. Despite consistently high lake levels, which imply greater ecosystem stability, the study discovered that species richness fell flat after the last arid period, based on data from fossilized pollen samples collected from the lakebed. This was surprising because, in previous climate cycles, rainy environments had produced forests that provided a rich habitat for a diverse range of species, according to Ivory.

“The pollen that we see in this most recent period of stable climate is very different from what we saw previously,” she said. “In particular, trees that indicate dense, structurally complex forest canopies are no longer common, and have been replaced by pollen from plants that tolerate frequent fire and disturbance.”

The researchers conclude that the increase in archaeological sites following the last arid period, combined with the increase in charcoal and lack of forest, suggests that people were manipulating the ecosystem with fire. The scale of their long-term environmental impact is more commonly associated with farmers and herders than with hunter-gatherers. This implies early ecological manipulation comparable to modern humans and may also explain why the archaeological record formed.

According to the researchers, the burning, combined with climate-driven changes, created the conditions that allowed for the preservation of millions of artifacts in the region. “Unless there’s something to stop it, dirt rolls downhill,” Wright explained. “When the trees are removed, there is a lot of dirt moving downhill in this environment when it rains.”

Previous transitions from dry to wet conditions in the region did not produce a similar alluvial fan and were not preceded by the same charcoal spike, according to the researchers. Thompson said it’s unclear why people were setting fire to the landscape. It’s possible they were experimenting with controlled burns to create mosaic habitats suitable for hunting and gathering, a behavior observed among hunter-gatherers. She explained that it was possible that their fires had become out of control, or that there were simply a large number of people burning fuel in their environment for warmth, cooking, or socialization.

“It’s caused by human activity in some way,” she explained. “It demonstrates that early people, over time, took control of their environment rather than being controlled by it. They altered entire landscapes, and our relationship with our environments continues to this day, for better or worse.”

The Australian Research Council, the National Geographic-Waitt Foundation, the Wenner-Gren Foundation, the University of Queensland Archaeological Field School, the Korean Research Foundation Global Research Network, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Emory University, and the Belmont Forum all provided funding for this research.