CRISPR therapy is a novel gene therapy that is injected directly into the eyes of visually impaired patients. This has significantly improved their vision and enabled them to see more color. NPR spoke with a number of study participants, all of whom had severe Leber congenital blindness. Despite their poor vision, they can navigate safely and find small objects with little assistance. One of the patients, Michael Kalberer, stated that after receiving the treatment, he was able to see color for the first time in many years.

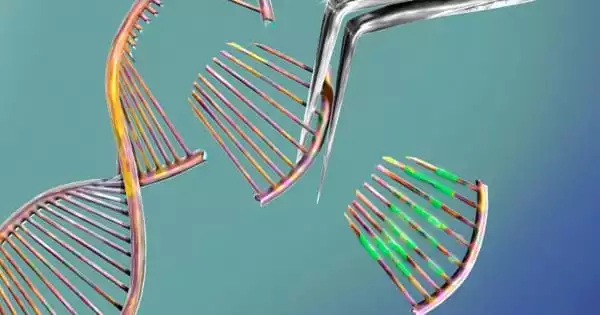

Seven patients agreed to participate in the study, in which doctors altered their DNA by injecting a gene-editing CRISPR directly into their cells. Researchers revealed on Wednesday that gene-editing therapy improved the vision of patients with leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), a severe form of vision impairment.

Several study participants, all of whom had a severe form of genetic vision impairment known as Leber congenital amaurosis, told NPR that they were ecstatic with their improved vision. While their eyesight is still far from perfect, they can now safely navigate their surroundings and find smaller objects with less assistance. And one, Michael Kalberer, said that the treatment gave him the ability to see color for the first time in years.

An experimental gene therapy that involves injecting CRISPR therapy directly into visually impaired patients’ eyeballs has vastly improved most volunteers’ vision, even allowing some to see color more vividly than ever before.

Michael Kalberer

In addition to being able to navigate and distinguish food on a plate, Kalberer told a story about going out to dinner with a friend and being taken aback by the sight of the color pink in the sky. “‘Yeah, you see the sunset,’ she says. “That’s the sunset,” he explained to NPR. “And then we both smiled at each other.” It was a fantastic moment.” Carlene Knight, another patient, said she can now see colors much more vividly and feels safer walking around at work.

“I was bumping into the cubicles and really scaring people who were sitting at them,” patient Carlene Knight said of her job before the treatment. “It’s lovely. I don’t scare people as much, and I don’t have as many bruises.”

Knight has since dyed her hair green in order to celebrate her newly discovered ability to see her favorite color.

People with the rare disorder are also more sensitive to light and have less sharp vision. There is no cure for it — or even for the more common types of color blindness, which affect only specific colors. In the future, however, a one-time treatment known as gene therapy may be able to help these people see in technicolor.

Viruses are used in gene therapy because of their natural ability to enter cells. However, the viruses have been modified so that they cannot cause infection, and they have also been engineered to carry healthy copies of a gene to compensate for a mutated one.

For years, scientists have imagined gene therapy as a means of treating red-green color blindness, the most common type of color vision deficiency in which people have difficulty distinguishing reds from greens. One in every twelve men suffers from this type of color blindness.

The majority of gene therapies currently being tested are indirect. Cells will be extracted from a volunteer’s body, treated, and then reintroduced into their system. Because that is not possible with the retina, the patients had to be treated with eye injections, according to NPR. However, the treatment appears to be effective, as researchers announced on Wednesday at the International Symposium on Retinal Degeneration that the majority of their patients, who had a severe type of genetic vision impairment known as Leber congenital amaurosis, were able to see far better than before.

“We’re overjoyed,” said Harvard Medical School ophthalmologist Eric Pierce, who is assisting with the experiment. “We’re ecstatic to see early signs of efficacy because it means gene editing is effective.” This is the first evidence that gene editing is working inside someone and improving — in this case — their visual function.”