Addressing the climate crisis will necessitate massive collaboration, but in order to do so, people must first understand the specific challenges that lie ahead and how to best proceed. People all over the world are feeling the effects of the climate crisis, but many are unsure how, or even if, they can address it.

Researchers from the University of Cape Town, South Africa, and the University of Connecticut published a study in Nature Climate Change today that looked at the rate of climate change literacy in Africa to determine the magnitude of the challenge. According to a recent survey conducted by the Afro barometer public opinion research network, more than two-thirds of Africans believe that climate conditions for agricultural production have deteriorated over the last ten years; 71 percent of Africans are aware of climate change and agree that it should be stopped, but only 51 percent are confident in their ability to make a difference.

According to Talbot Andrews, an assistant professor of political science and co-author of the study, “Climate change is changing the environment, and people must adapt. People who are more knowledgeable about climate change and have a better understanding of what is to come will be able to adapt more effectively. Increasing climate change literacy will go a long way toward ensuring that people are prepared for the future.”

Despite the study’s focus on Africa, climate change will bring economic and environmental challenges as well as opportunities all over the world, and those who understand the risks will be better prepared to respond.

Addressing the climate crisis will require cooperation on a massive scale, but to accomplish this, people need to know what specific challenges lie ahead and how to best move forward.

“Anticipating climate change in decisions about their livelihoods, careers, and investments will help everyday Africans safeguard their futures,” says Nicholas Simpson, a researcher at the University of Cape Town. “Without climate change literacy or an understanding of the human causes of climate change and its potential global impact, hundreds of millions of people in Africa will be unable to adequately adapt to climate change.”

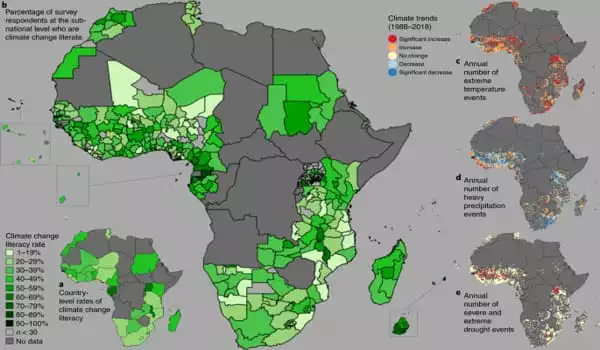

The researchers set out to quantify climate change literacy rates in Africa as well as identify the major social and environmental predictors of climate change literacy across the continent. Though climate change literacy underpins more informed responses to climate change, little is known about national and subnational variation in climate change literacy in Africa, as well as the drivers of this variation.

The researchers conducted a meta-analysis of previous research identifying the drivers of climate change literacy in Africa, followed by their own analysis combining public opinion and environmental data. Their primary data source was Afro barometer, Africa’s largest public opinion survey, which was conducted between 2016 and 2018 on nationally representative samples of 44,623 people in 33 countries, representing 61 percent of the African population. Climate change literacy was assessed, as well as perceptions of climate change and sociodemographic factors such as age, gender, education, and wealth.

There had previously been no multi-country study to estimate how many Africans were aware of climate change and its anthropogenic causes. Previously published studies focused primarily on perceptions of climate and weather changes in Africa, often only among specific groups within a given country, rather than climate change awareness and literacy on a larger scale.

“By far the best predictor of climate literacy is education, and what’s great about education is that it works equally well for men and women,” Andrews says. “There is a significant gender gap in climate change literacy, but education is helping to close it. We also see that wealthier and more mobile Africans are much more likely to be climate change literate, whereas poor Africans are much less likely. People who are poorer and more vulnerable, on the other hand, are more likely to notice environmental changes and see how things like precipitation and drought are changing.”

In Africa, the average national climate change literacy rate is 37%. According to co-author and University of Cape Town researcher Chris Trisos, this is significant because “climate change literacy rates are generally over 80% in Europe and North America, highlighting a severe deficit for Africa.”

There is also a gender disparity in climate change literacy, with men outnumbering women in every country.

“These are troubling findings, given that women are frequently more vulnerable to climate impacts than men,” Andrews says. “Because of power disparities and gender dynamics, women are far more vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Men have a higher socioeconomic status, more political power, and more household power. The types of adaptation that families and communities use to prepare for climate change are driven by men and do not always address the vulnerabilities that women face.”

However, the researchers conclude that education is generally equally effective in increasing both men’s and women’s climate change literacy. These findings suggest that education will be a critical tool in closing the climate change literacy gap between Africa, Europe, and North America, as well as the gender gap in climate change literacy within the African continent.

These findings can assist policymakers in developing and implementing interventions to increase climate change literacy. In the near future, Africa is expected to experience significant shifts in urbanization, education, gender equality, mobility, and income. As a result, rates of climate change literacy are likely to change in tandem with these processes and changing climate hazards.

The researchers’ next steps will be to replicate these findings in the 8th round of Afro barometer survey data and look for variations in rates for countries between the 2017 and 2021 surveys, as well as updated climate data.

Andrews is also working on studies focusing on the urban/rural divide in the United States, where education plays a role in climate literacy. “Climate change is much more polarized in the United States, with a large democrat/republican divide that parallels the urban/rural divide. It is difficult to separate those factors. However, the environment is changing as a result of climate change, and people must adapt “According to Andrews.