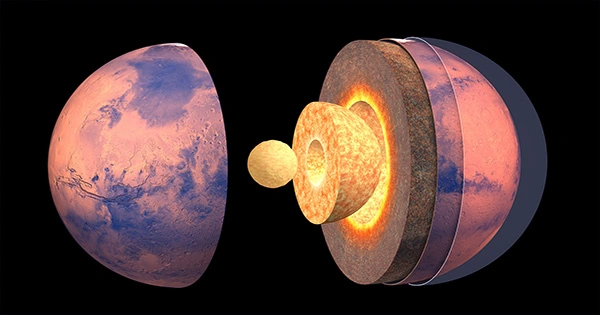

Many tiny marsquakes have been discovered by NASA’s InSight Mars lander, especially in a location known as Cerberus Fossae. The origin of 47 quakes has been shown to be volcanic rather than tectonic. If that’s the case, it suggests the period of Martian volcanoes isn’t gone yet – but we shouldn’t expect to see massive eruptions covering the skies with ash. There are two types of earthquakes on Earth, excluding those caused by human action. When plates travel past or beneath one other, tectonic earthquakes occur. Volcanic earthquakes occur when magma moves quickly or when gas pressure builds up in the crust. Other worlds have neither, with their surfaces merely swaying in response to external events like meteor strikes, but what about Mars?

The study was published in the journal Nature Communications. Professor Hrvoje Tkali of the Australian National University and Dr. Weijia Sun of the Chinese Academy of Sciences have questioned whether the quakes observed by Insight’s seismometers are tectonic in nature, signaling that Mars still possesses movable magma in its mantle. That tongue-twister might make the geology of Mars more fascinating and point us in the right direction for future geological research. It’s no secret that Mars was formerly volcanic; Olympus Mons, the Solar System’s greatest volcano, bears witness to this. It’s over twice the height of Everest, at 21.9 kilometers (13.6 miles). In the Tharsis Montes volcanic zone, there are several other massive volcanoes.

Olympus Mons, on the other hand, originated almost three billion years ago and hasn’t erupted in hundreds of millions of years. Other known volcanoes on Mars are significantly older. Some planetary scientists believe we may have lost the opportunity to see a Martian volcano erupt, but Tkali isn’t so sure. Tkali told IFLScience, “InSight has observed high and low frequency quakes.” “We only looked at low-frequency quakes in our article.” We discovered that some of them are repeated in ways that tectonic quakes cannot explain.”

Tkali and Sun investigated for analogous instances on Earth and discovered similar wave patterns in latent volcanic quakes. As a result, they determined that these quakes are almost certainly volcanic. That doesn’t rule out the possibility of lava and ash erupting from a new Martian mountain. “Martian volcanism is intrusive volcanism,” Tkali told IFLScience. “Magma doesn’t find a path to the top.” The thickness of the Martian crust in comparison to the planet’s size, as well as the chemical characteristics and temperature of the magma, may be the causes for this. Planetary scientists may be excited by a new rising, even though others may prefer the sight of explosions.

The Cerberus Fossae quakes were originally assumed to be tectonic, according to Tkali, since the fissures and steep faults that give the area its name imply tectonic activity in the recent past. There was no reason to believe there was another area of rising magma almost 1,000 kilometers away from the Tharis Montes province. The quakes are minor, with none above magnitude 4 – but Tkali told IFLScience that this may not always be the case, as seen by recent magnitude-7 activity on Mars, the kind that destroys cities on Earth.

Previous attempts to use InSight to detect quakes have had difficulty distinguishing motions from noise created by the Martian wind, frequently succeeding only late at night when the wind has died down. “We discovered that these marsquakes frequently occurred at all hours of the Martian day,” Tkali said in a statement, using more advanced processing methods to distinguish signal from noise. This ruled out the notion that what was previously found was due to temperature modifications due to the considerable difference in day and night temperatures.