In the first archaeobotanical analysis of burnt food remnants on the surface of pottery vessels, researchers from Kiel University’s Collaborative Research Center (CRC) 1266 were able to demonstrate the variety of meals prepared in Eastern Holstein 5,000 years ago.

According to the research, which was published in PLOS ONE, cereals and wild plants both had a significant impact.

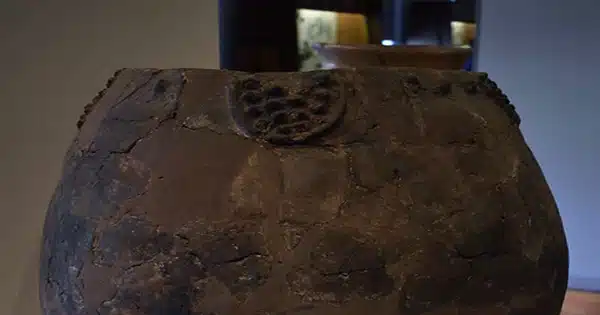

The pottery jars under analysis originate from Oldenburg LA 77 at Ostholstein, a Neolithic settlement that is among Schleswig-Holstein’s oldest villages. SEM scanning and chemical analysis were used to identify a highly developed plant-based meal preparation.

According to Professor Wiebke Kirleis, who is leading the research in CRC 1266, “the ‘food crusts’ contained tissue remnants of emmer and barley grains, as well as seeds from the white goosefoot, a wild plant that grows as a weed and ruderal plant and produces many starchy seeds.”

“Archaeobotanical analyses of soil samples from this Neolithic settlement have already documented burned grains and chaff from emmer and barley, as well as seeds from white goosefoot,” continues Dr. Dragana Filipović, research associate at the CRC 1266.

Milky ripe cereals and wild plants provided variety: The new research demonstrates that wild plants expanded the earliest farmers’ food source and that grains did play a significant part in the diet. When the barley was milky mature, it was picked and treated similarly to the typical Baden-Württemberg green spelled. Because the emmer was prepared while still sprouting, the porridge had a pleasant taste.

Thus, food throughout the Neolithic Period was diversified rather than bland. Individuals valued good flavor much and had very distinct senses of taste.

Thus far, the pottery’s chemical studies have demonstrated that the receptacles held dairy items. Examining the crusts that have burned onto the cooking pot reveals that grains and dairy items were likely processed into porridge for daily use in the same containers and served as a foundation for a well-balanced diet.

“The plant food components can only be detected in the burnt food crust, while the animal fats are absorbed into the ceramic and leave a signal there,” explains Dr. Lucy Kubiak-Martens, the study’s first author and collaboration partner of BIAX Consult (Netherlands).

This demonstrates the significance of using many methods to reconstruct Neolithic cuisine made using a range of ingredients. These findings deepen our knowledge of the protracted and intricate process of turning plants into food in the era that followed the arrival of cultivated plants and the agricultural way of life in north-central Europe.