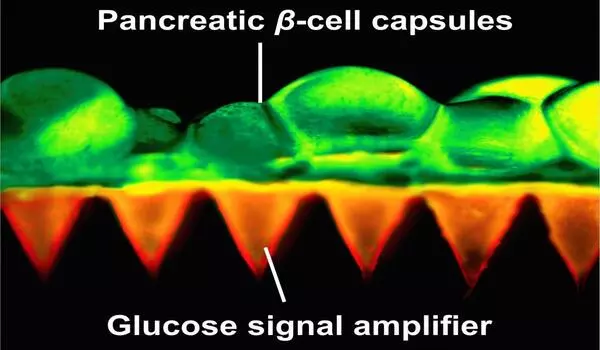

Diabetes care has seen ongoing research and development, including advancements in insulin-producing cells. One noteworthy area of study is the use of stem cells to generate insulin-producing cells. Scientists are investigating ways to generate functional beta cells from stem cells, which are pancreatic cells that produce insulin. This method has the potential to provide a renewable and potentially infinite supply of insulin-producing cells for diabetes treatment.

A team from the University of Alberta has developed a new step in the process of creating insulin-producing pancreatic cells from a patient’s own stem cells, bringing the prospect of injection-free diabetes treatment closer to reality.

In a process known as “directed differentiation,” the researchers take stem cells from a single patient’s blood and chemically wind them back in time, then forward again to eventually become insulin-producing cells.

We need a stem cell solution that provides a potentially limitless source of cells. We need a way to make those cells so that they can’t be seen and recognized as foreign by the body’s immune system.

James Shapiro

The team used the AKT/P70 inhibitor AT7867 to treat pancreatic progenitor cells in a study published this month. They claim that the method produced the desired cells at a rate of 90%, compared to previous methods that produced only 60% target cells. When transplanted into mice, the new cells were less likely to form unwanted cysts and resulted in insulin-free glucose control in half the time. The team believes its efforts will soon be able to eliminate the final five to 10 percent of cells that do not result in pancreatic cells.

“We need a stem cell solution that provides a potentially limitless source of cells,” says James Shapiro, Canada Research Chair in Transplant Surgery and Regenerative Medicine and head of the Edmonton Protocol, which has allowed 750 transplantations of donated islet cells since it was first developed 21 years ago. “We need a way to make those cells so that they can’t be seen and recognized as foreign by the body’s immune system.”

The researchers believe that this safer and more reliable method of growing insulin-producing cells from a patient’s own blood may one day allow for transplants without the use of anti-rejection drugs. Recipients of donated cells must take anti-rejection drugs for the rest of their lives, and the therapy is limited by the scarcity of donated organs.

More safety and efficacy studies are needed, according to Shapiro, before stem-cell-derived islet cell transplantation is ready for human trials, but he is encouraged by the progress.

“What we’re trying to do here is peer over the horizon and try to imagine what diabetes care is going to look like 15, 20, 30 years from now,” he says. “I don’t think people will be injecting insulin anymore. I don’t think they’ll be wearing pumps and sensors.”