Scientists are investigating various methods for people with disabilities to communicate with their thoughts. The most recent and fastest trend is a return to a time-honored method of self-expression: handwriting.

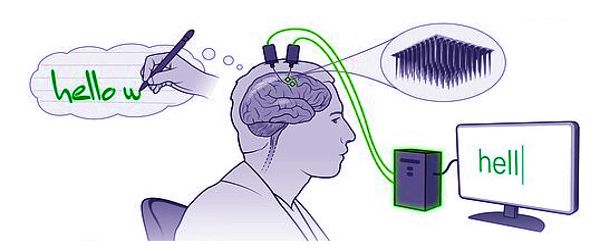

Researchers have deciphered the brain activity associated with attempting to write letters by hand for the first time. The team used an algorithm to identify letters as he attempted to write them while working with a participant with paralysis who has sensors implanted in his brain. The text was then displayed on a screen in real-time by the system.

According to study co-author Krishna Shenoy, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator at Stanford University who co-supervised the work with Jamie Henderson, a Stanford neurosurgeon, with further development, the innovation could allow people with paralysis to rapidly type without using their hands.

Researchers have, for the first time, decoded the neural signals associated with writing letters, then displayed typed versions of these letters in real-time. They hope their invention could one day help people with paralysis communicate.

The study participant typed 90 characters per minute while attempting handwriting, more than doubling the previous record for typing with such a “brain-computer interface,” Shenoy and his colleagues report in the journal Nature.

According to Jose Carmena, a neural engineer at the University of California, Berkeley who was not involved in the study, this technology and others like it have the potential to help people with a wide range of disabilities. “It’s a big advancement in the field,” he says, despite the fact that the findings are preliminary.

Brain-computer interfaces convert thought into action, Carmena says. “This paper is a perfect example: the interface decodes the thought of writing and produces the action.”

Thought-powered communication

When a person’s ability to move is lost due to an injury or disease, the brain’s neural activity for walking, grabbing a cup of coffee, or speaking a sentence remains. Researchers can use this activity to help people who have lost abilities due to paralysis or amputation regain them.

The requirement varies according to the disability. Some people who have lost their hand use can still use a computer with speech recognition and other software. Scientists have been working on alternative communication methods for those who have difficulty speaking.

Shenoy’s team has recently decoded the neural activity associated with speech in the hopes of reproducing it. They have also devised a method for participants with implanted sensors to move a cursor on a screen by using their thoughts associated with attempted arm movements. By pointing at and clicking on letters in this manner, people were able to type approximately 40 characters per minute, breaking the previous speed record for typing with a brain-computer interface (BCI).

However, no one had examined the handwriting. Frank Willett, a neuroscientist in Shenoy’s lab, wondered if it was possible to harness the brain signals elicited by writing. “We want to find new ways to allow people to communicate more quickly,” he says. He was also motivated by the chance to try something new.

The team collaborated with a participant in the BrainGate2 clinical trial, which is evaluating the safety of BCIs that relay information directly from a participant’s brain to a computer. (Leigh Hochberg, a neurologist, and neuroscientist at Massachusetts General Hospital, Brown University, and the Providence VA Medical Center, is the trial’s director.) Henderson implanted two tiny sensors into the area of the brain that controls the hand and arm, allowing the person to move a robotic arm or a cursor on a screen by attempting to move their own paralyzed arm.

The participant, who was 65 years old at the time of the study, was paralyzed from the neck down due to a spinal cord injury. A machine learning algorithm recognized the patterns his brain produced with each letter by using signals picked up by the sensors from individual neurons while the man imagined writing. The man could use this system to copy sentences and answer questions at a rate comparable to someone his age typing on a smartphone.

According to Willett, the “Brain-to-Text” BCI is so fast because each letter elicits a highly distinct activity pattern, making it relatively easy for the algorithm to distinguish one from another.

A new system

Shenoy’s team envisions using attempted handwriting for text entry as part of a larger system that also includes point-and-click navigation, similar to that found on today’s smartphones, and even attempted speech decoding. “Having those two or three modes and switching between them comes naturally to us,” he says.

The team will then work with a participant who is unable to speak, such as someone with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a degenerative neurological disorder that causes loss of movement and speech, according to Shenoy.

Henderson adds that the new system could potentially help people who are paralyzed due to a variety of conditions. Among these are brain stem strokes, which afflicted Jean-Dominique Bauby, author of The Diving Bell and the Butterfly. “He was able to write this moving and beautiful book by painstakingly selecting characters one at a time, using eye movement,” Henderson says. “Imagine what he could have done if Frank’s handwriting interface had been available!”