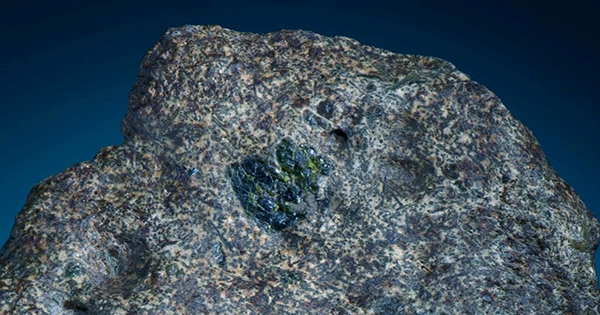

The Winchcombe meteorite has undergone new research, which has demonstrated just how quickly the atmosphere may contaminate space objects that fall to Earth.

The meteorite was the first to be discovered on UK soil in almost 30 years when it landed in Gloucestershire in February of last year.

A domestic driveway contained fragments that were found several hours after it reached the atmosphere. Six days later, further parts were discovered in a sheep field.

The findings demonstrate that despite the meteorites’ speedy recovery, the fragments immediately through numerous “terrestrial phases”—salts and minerals that formed from their surfaces interacting with the moist environment in where they landed.

The results might guide future initiatives to safeguard newly discovered meteorites. They might also assist geological trips to asteroids and other planets in ensuring that their samples are clear of pollutants from Earth when they return to our world.

Laura Jenkins, a student at the School of Geographical & Earth Sciences at the University of Glasgow, is the paper’s primary author.

She stated: “Understanding the asteroids they came from and how they formed can be gained through analysis of meteorites. The asteroids that accompany Winchcombe and other meteorites like it may have brought water to Earth, providing it with enough water to build its distinctive oceans. Winchcombe and other meteorites like it contain extraterrestrial water and organics.”

However, a meteorite alters and loses information when exposed to pollutants from the earth, particularly moisture and oxygen.

A team of academics led by the University of Glasgow investigated two tiny fragments of Winchcombe for indications of terrestrial alterations and described their findings in a new publication published in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

They examined the samples’ surfaces using transmission electron microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and Raman spectroscopy. The fragments from the driveway were used for one sample, and those from the sheep field were used for the other.

They discovered that the fusion crust of samples taken from the sheep field had two types of salt—sulfates of calcium and calcite—formed on it. Meanwhile, they noticed that the sample obtained from the driveway included halite, also known as table salt.

When meteorites melt during their ferocious entrance into the Earth’s atmosphere, a peculiar substance called the fusion crust is created. The scientists come to the conclusion that since the sulfates were found on the fusion crust’s exterior, they most likely formed after the object touched down due to exposure to the moist conditions of the sheep field.

“In addition to aiding in our knowledge of their creation, knowing which phases in meteorites like Winchcombe are extraterrestrial and which are terrestrial can help us relate meteorites that have landed on Earth to samples returned by sample return missions. The asteroids in our solar system and their impact on the evolution of Earth can be better understood.”

Dr. Luke Daly, one of the paper’s co-authors, is a lecturer at the University of Glasgow and a member of UKFall, the observation network that discovered the Winchcombe meteorite and determined its landing location.

The largest fragment of the Winchcombe meteorite was found in a sheep field by volunteer Mira Ihasz, and Dr. Daly headed the search team that found it.

We have always known that meteorites’ surfaces are impacted by exposure to the atmosphere, but this is the first time we have been able to observe how quickly the process may get started and develop, the scientist claimed.

“Thanks to the monitoring of the UKFall network and the efforts of the volunteers who helped us recover the largest pieces from the field, we were very fortunate to be able to recover the Winchcombe meteorite so fast.”

This study emphasizes how important it is to continue keeping an eye on the skies and to form search teams as soon as meteorites are sighted.