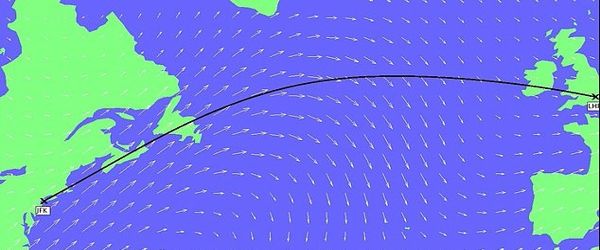

Researchers found that flights between London and New York may have used up to 16% less fuel by more reliably following jet stream tailwinds or ignoring headwinds, at a fraction of the expense of other emissions-cutting technologies. Airlines could save fuel and reduce carbon on transatlantic flights by making a smoother ride on the jet stream, recent research has shown.

Scientists at the University of Reading discovered that commercial flights between New York and London last winter could have used up to 16% less fuel if they had made greater use of fast-moving winds at altitude.

In the near future, new satellites would enable transatlantic flights to be monitored more precisely while staying a safe distance apart. This opportunity could make it possible for aircraft to be more agile in their flight patterns, more precisely to follow favorable tailwinds and prevent headwinds, giving the aviation industry a cheaper and more immediate way to reduce emissions than by technological advancements.

Passenger aircraft could cut fuel costs and carbon emissions by taking better advantage of favorable winds at altitude, a new study reveals. Transatlantic aircraft could use 16 % less fuel by hitching a better ride on the jet stream, study claims.

Intercontinental flights across the Atlantic Ocean could travel a lot longer distances and use more fuel than is required, researchers claim in a new Environmental Science Letters report. Instead, by better coasting on jet streams that orbit the globe, they could quickly reduce their fuel consumption and emissions. The aviation sector is under pressure to reduce its greenhouse gas and other emissions and has taken measures to decarbonize. Aircraft are smaller and more fuel-efficient than they used to be. A few airlines have continued to use biofuel blends. Small hybrid-electric and battery-powered electrical aircraft are beginning to take off, and Airbus is looking at hydrogen-powered zero-emission aircraft.

Cathie Wells, PhD researcher in mathematics at the University of Reading and lead research author, said: “Current transatlantic flight paths mean that aircraft waste more fuel and release more carbon dioxide than they require.” While winds are to some extent taken into account when preparing routes, factors such as reducing the overall cost of running a flight are currently given a higher priority than minimizing fuel burns and emissions.”

“Simple tweaks to flight paths are far cheaper and can offer benefits immediately. This is important because lower emissions from aviation are urgently needed to reduce the future impacts of climate change.”

The latest report, published today in Environmental Research Letters, analyzed some 35,000 flights in both directions between New York and London between 1 December 2019 and 29 February 2020. The team contrasted the fuel used during these flights with the fastest path available at the time by traveling into or through the east jet stream of air currents.

Scientists also found that making greater use of winds would save about 200 kilometers of fuel per flight on average, leading to a potential loss of 6.7 million kilograms of carbon dioxide emissions during the winter season. The average fuel savings per flight was 1.7% when flying west to New York and 2.5% when flying east to London. The research was conducted by the University of Reading in partnership with the United Kingdom National Center for Earth Observation, the University of Nottingham, and Poll AeroSciences Ltd.

Aviation is reportedly responsible for about 2.4% of all human-caused carbon emissions, and this number is growing. The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and countries around the world have responded by establishing measures to increase the fuel efficiency of international flights or offset emissions, but much of this action depends on technical innovations and is thus expensive and slow to enforce.

Through following more versatile paths, aircraft could benefit from high-altitude air currents as they move east, and could prevent headwinds that slow them down as they move in the other direction. Current flight tracks take wind into account, but are not built to be effective and versatile, says Wells. “By being more mobile, it is possible to enter wind pockets that may not be available on a straight line between the entry and exit points.”

Climate change is expected to have a major effect on air transport, with previous Reading reports finding that flights will experience two or three times more extreme clear-air turbulence if emissions are not reduced.