Researchers discovered that the composition of a baby’s first feces – a thick, dark green substance known as meconium – is linked to whether or not a child develops allergies during their first year of life. They show that the development of a healthy immune system and microbiota may begin before a child is born by analyzing meconium samples from 100 infants.

Less allergies are associated with a metabolically diverse meconium, which indicates the initial food source for the gut microbiota. The study suggests possible early interventions to prevent or treat allergies shortly after birth. The contents of a baby’s first diaper may appear to be an unusual place to look for answers, but they can reveal a lot about a newborn’s future health.

In a new study published today in Cell Reports Medicine, a team of University of British Columbia (UBC) researchers discovered that the composition of a baby’s first poop – a thick, dark green substance known as meconium – is related to whether or not a child develops allergies within the first year of life.

“Our analysis revealed that newborns who developed allergic sensitization by one year of age had significantly less ‘rich’ meconium at birth, compared to those who did not develop allergic sensitization,” says Dr. Brett Finlay, senior co-author of the study and professor at UBC’s Michael Smith Laboratories and departments of biochemistry and molecular biology, microbiology and immunology.

A new study finds that the contents of an infants’ first stool, known as meconium, can predict if they’ll develop allergies with a high degree of accuracy.

Infants with less diverse metabolic niches for the first microbes to settle in the gut had the highest risk of developing allergies a year later. Many of these elements were linked to the presence or absence of various bacterial groups in the child’s digestive system, which play an increasingly important role in our overall health and development.

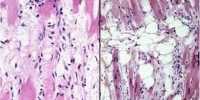

Meconium, which is typically excreted on the first day of life, is composed of a variety of materials ingested and excreted during development, including skin cells, amniotic fluid, and various molecules known as metabolites.

“Meconium acts as a time capsule, revealing what the infant was exposed to prior to birth. It contains a wide range of molecules encountered and accumulated from the mother while in the womb, and it serves as the first food source for the earliest gut microbes “Dr. Charisse Petersen, a research associate in the department of pediatrics at UBC, is the study’s lead author.

The researchers analyzed meconium samples from 100 infants in the CHILD Cohort Study (CHILD), a world-leading birth cohort study in maternal, newborn, and child health research.

They discovered that the fewer different types of molecules in a baby’s meconium, the greater the child’s one-year risk of developing allergies. They also discovered that a decrease in certain molecules was linked to changes in key bacterial groups. These bacteria groups play an important role in the development and maturation of the microbiota, a vast ecosystem of gut microbes that is a powerful player in health and disease.

“This research suggests that the development of a healthy immune system and microbiota may begin well before a child is born – and that the tiny molecules an infant is exposed to in the womb play a critical role in future health,” says Dr. Petersen.

Using a machine-learning algorithm, the researchers combined meconium, microbe, and clinical data to predict whether or not an infant would develop allergies by one year of age with a high degree of accuracy (76%), and more reliably than ever before.

The study findings have important implications for at-risk infants, say the researchers.

“We know that children who have allergies are more likely to develop asthma. We now have the ability to identify at-risk infants who could benefit from early interventions before they show signs and symptoms of allergies or asthma later in life “Dr. Stuart Turvey, a professor in UBC’s department of pediatrics, investigator at BC Children’s Hospital, and co-director of the CHILD Cohort Study, is the study’s senior co-author.

Increased diversity of metabolic products in the meconium promotes the development of “healthy” bacteria families, such as Peptostreptococcaceae, which in turn promotes the development of a healthy and diverse gut microbiome. Ultimately, such diversity reduces the likelihood of a child developing allergies.