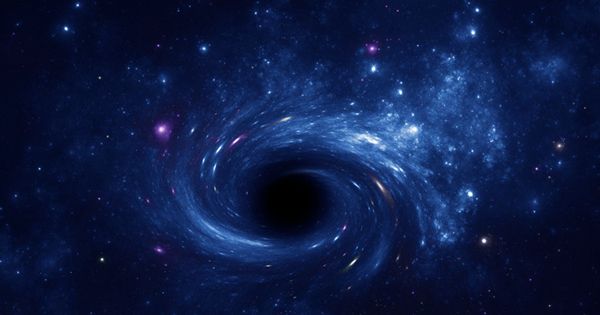

The gravitational waves that our earth-based detectors capture is not just present in the universe. Scientists hope that more subtle and steady squabbles will divide the universe, known as the gravitational wave background. Researchers have now reported the first possible indication of detection. Detecting gravitational waves from black holes or neutron star collisions is no easy task. Gravitational waves compress and distort space-time but only by a fraction of the size of an atom. For the gravitational wave background, the researchers had to be more creative with how they wanted it.

“Galaxy-Sized” Space Observatory May Have Detected Subtle Gravitational Waves Background

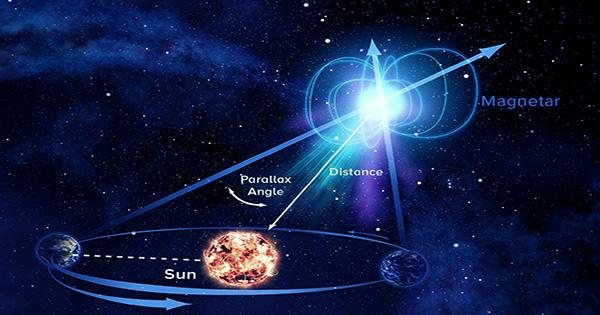

Insert the pulsar. Pulsars are neutron stars that move at extremely regular intervals, a feature that makes them an incredible cosmic clock. A joint US-Canadian project, the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav), has observed pulsars across the Milky Way as the Milky Way gravitational wave observatory. Changes during pulsar pulses can be a gravitational wave signal but it requires many data to confirm and understand.

In the Astrophysical Journal Letter, the team reported finding the first exciting results from a low-frequency signal from 13 years of data. The team was able to rule out many sources of errors and effects without relating to such gravitational waves in our own solar system. What remains is a strong indication that the gravitational-wave background may be.

Lead author Dr. Joseph Simon, from the University of Colorado Boulder, said in a statement, “It’s incredibly exciting to get such a strong signal out of the data.” “However, since we are exploring the gravitational-wave signal that extends the entire duration of our observation, we need to understand it carefully. This leaves us in an interesting place, where we can strongly rule out the origin of some familiar sound, but we still cannot say whether the signal is actually from gravitational waves, for which we will need more data.”

Once the gravitational wave background signal is confirmed, it will provide a new look into some of the mysteries of the universe, such as how supermassive black holes at the center of the galaxy merge. For physicists, it has been on the rise for some time.

Professor Julie Comerford, also of CU Boulder and a NANOGrav team member said, in a statement, “These first indications of a gravitational wave background suggest that supermassive black holes are probably merging, and in the ocean of gravitational waves we are spreading from supermassive black hole attachments to galaxies across the universe.” There is a bittersweet note of this work, practically presented at the 237th meeting of the American Astronomical Society. A huge chunk of the data collection has been broken down last year and now decommissioned.