A landmark scientific study involving marine biologists from Greece, Turkey, Cyprus, Libya, Italy, Tunisia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Malta has just been published, documenting instances where native Mediterranean species preyed on two highly invasive marine fish—the Pacific red lionfish and the silver-cheeked toadfish. Prof. Alan Deidun, the coordinator of the Spot the Alien Fish citizen science campaign and a resident academic in the Faculty of Science’s Department of Geosciences, is a co-author of such a comprehensive study.

The Pacific red lionfish (Pterois miles) and the silver-cheeked toadfish (Lagocephalus sceleratus) are two of the most invasive non-indigenous fish species to have entered the Mediterranean in recent years, posing ecological and socioeconomic risks. For example, significant negative impacts on native fish populations in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico have been documented as a result of the introduction of non-native lionfish species, to the point where conservation biologists in invaded areas advocate active removal and even consumption of the species, owing to a lack of predators of the same species.

Investigating how to control invasive marine species through the use of food chains. The study has documented only one native predator of adult silver-cheeked toadfish—loggerhead turtles—and a number of native predators for juvenile toadfish, including dolphinfish and garfish.

Furthermore, lionfish pose a risk to humans because the venom in their 18 spines can cause cardiovascular and neuromuscular effects ranging from mild reactions, such as swelling, to extreme pain and paralysis in the upper and lower extremities. The Pacific red lionfish was first discovered in Israeli waters in 1991, and it has since spread to the central Mediterranean in Italy and Tunisia, but not to Maltese waters.

The silver-cheeked toadfish was first discovered in the Mediterranean in Turkish waters in 2003, and it has since been caught several times in Maltese waters as of 2016. This species is extremely toxic due to high concentrations of the potent neurotoxin tetrodotoxin (TTX) in its tissues, which is responsible for a number of human deaths each year. Furthermore, the species disrupts fishing lines, tears fishing nets, and predates on fished stocks, such as cephalopods (squid, cuttlefish, and octopus), causing significant socioeconomic impact.

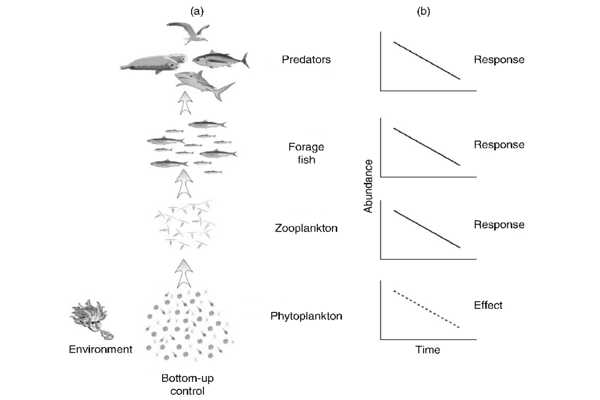

An invasive species is an organism that has been introduced and has a negative impact on its new environment. Despite the fact that their spread can be beneficial, invasive species have a negative impact on the invaded habitats and bioregions, causing ecological, environmental, and/or economic damage. The term is also applied to native species that have become invasive in certain ecosystems as a result of human-caused environmental changes. The purple sea urchin is an example of a native invasive species that has decimated natural kelp forests along the northern California coast as a result of the historic overhunting of its natural predator, the California sea otter. In the 21st century, invasive species have become a serious economic, social, and environmental threat.

The study found only one native predator of adult silver-cheeked toadfish, loggerhead turtles, and a number of juvenile toadfish predators, including dolphinfish and garfish. Cannibalism has been observed within the species as well. The dusky grouper, white grouper, common octopus, and the silver-cheeked toadfish were all documented native predators of the Pacific red lionfish. Through a trans-Atlantic research collaboration with colleagues from the United States, the study also documented predation of the two invasive fish species within their native range (i.e., the Indo-Pacific region) as well as from other invaded regions (e.g., the western Atlantic).

Due to the scarcity of natural, native predators of these two highly invasive non-indigenous fish species, direct human management measures are required to control their Mediterranean populations. In Cyprus, for example, authorities incentivize direct removal of both silver-cheeked toadfish and Pacific red lionfish individuals through the provision of financial ‘bounties’ and the organization of spearfishing competitions known as ‘derbies.’

Invasion of long-established ecosystems by organisms is a natural phenomenon, but human-facilitated introductions have increased the rate, scale, and geographic range of invasion significantly. Humans have served as both accidental and deliberate dispersal agents for millennia, beginning with their earliest migrations, accelerating during the age of discovery, and accelerating again during the age of international trade. The kudzu vine, Andean pampas grass, English ivy, Japanese knotweed, and yellow starthistle are all examples of invasive plant species.