Researchers created a light-emitting electrochemical cell out of dendrimers, a prominent material in the industry. Furthermore, the researchers discovered that employing biomass-derived cellulose acetate as the electrolyte preserves the cell’s long-life span. The cell, when combined with a graphene electrode, has the potential to pave the way for a future of environmentally benign and flexible light-emitting gadgets.

Researchers from Japan and Germany have constructed eco-friendly light-emitting electrochemical cells using novel molecules called dendrimers in conjunction with biomass-derived electrolytes and graphene-based electrodes, which could usher in a new era in illumination. Their research was published in Advanced Functional Materials.

Electroluminescence is the phenomenon in which a material generates light in response to an electric current running through it. Everything from the screen you’re reading this text to the lasers utilised in cutting-edge scientific study is a result of diverse materials’ electroluminescence. Because of its pervasiveness and importance in the current day, it is only natural that significant resources are invested in research and development to improve this technology.

Our research teams have been exploring new organic materials that can be used in LECs. One such candidate are dendrimers. These are branched symmetric polymeric molecules whose unique structure has led to their utility in everything from medicine to sensors, and now in optics.

Prof. Rubén D. Costa

“One such example of an emerging technology is ‘light-emitting electrochemical cells’ or LECs,” says Associate Professor Ken Albrecht of Kyushu University’s Institute for Materials Chemistry and Engineering, one of the study’s leaders. “They’ve gotten a lot of attention because of their lower cost than organic light emitting diodes, or OLEDs.” Another factor contributing to LECs’ success is their streamlined structure.”

OLED devices often necessitate the careful stacking of several organic layers, making production difficult and costly. LECs, on the other hand, can be created by combining a single layer of organic film with light-emitting components and an electrolyte. In contrast to the rare or heavy metals used in OLEDs, the electrode that ties everything together can even be constructed of simple materials. Moreover, LECs have lower driving voltage, meaning they consume less energy.

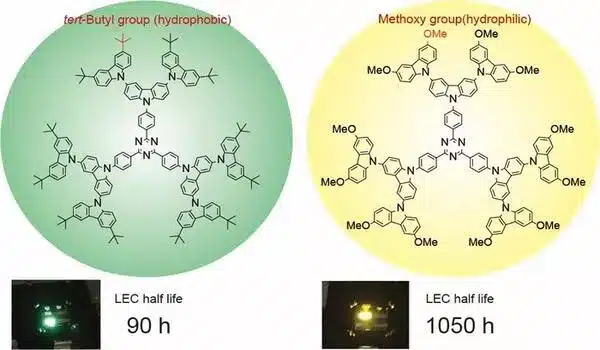

“Our research teams have been exploring new organic materials that can be used in LECs. One such candidate are dendrimers,” explains Prof. Rubén D. Costa of the Technical University of Munich, who led the research team in Germany. “These are branched symmetric polymeric molecules whose unique structure has led to their utility in everything from medicine to sensors, and now in optics.”

Building upon their past work on developing dendrimers, the research team began modifying their materials for LECs.

“The dendrimer we developed initially had hydrophobic, or water repelling, molecular groups. By replacing this with hydrophilic, or water liking, groups we found that the lifetime of the LEC device could be extended to over 1000 hours, more than 10-fold from the original,” explains Albrecht. “What makes it even better is that thanks to our collaboration with Dr Costa’s team the device is very eco-friendly.”

Costa’s team in Germany has been working for years on finding less expensive and more environmentally friendly materials for light-emitting devices. Cellulose acetate, a common organic substance used in everything from garment fibres to eyeglass frames, is one of the materials they’ve been experimenting with.

“We used biomass-derived cellulose acetate as the electrolyte in our new LEC device, and we confirmed that it has the same long-life span,” Costa says. “We also discovered that graphene can be used as an electrode.” This is a critical step towards creating ecologically friendly flexible light-emitting systems.”

While their work seems promising, the team explains that additional research is required before the gadgets can be commercialised.

“Because the device we built here only illuminates in yellow, we need to improve it so that it illuminates in the three primary light colours: blue, green, and red.” “Luminescence efficiency, or how bright the light is, also requires improvement,” Albrecht concludes. “However, the future appears bright thanks to our international collaboration.”