Marie Skodowska-Curie was weeks away from receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in November 1911. She won her first Nobel Prize for Physics in 1903, and the current prize made her the first woman to win two Nobel Prizes. She is still the only individual who has received honors in two distinct fields. Despite the fact that her outstanding job as a scientist should have been the focus of everyone’s attention, it appeared that many people were more interested in her personal life. Marie Curie became a widow after Pierre Curie died in 1906. She got romantically linked with scientist Paul Langevin, who had been Pierre’s PhD student, a few years later.

Despite the fact that Langevin and his wife were divorced, they were still legally married. The romance was causing problems in the Langevin household, but nothing compared to what was going to happen in public. In the fall of 1911, Curie, Langevin, and approximately 20 other scientists were invited to an exclusive, invitation-only symposium in Brussels. During this period, Langevin’s wife distributed love letters between Curie and Langevin to members of the media, portraying Curie as a wicked housewife.

If the rabble continues to consume your time, simply refuse to read the nonsense and leave it to the reptile for whom it was written. Curie was hailed by a throng when she went home to France after the meeting, which encircled her house and horrified Curie’s kids, who were just 7 and 14 years old at the time. Until the incident settled down, Curie and her girls briefly moved in with a friend.

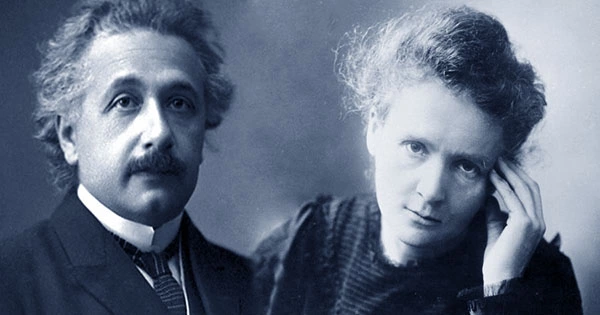

The acts of the media angered Albert Einstein, who had only recently met Curie at the Brussels meeting, causing him to send this letter to his new friend: Don’t laugh at me for not having anything decent to say when I wrote you. But I’m so angered by the public’s current obsession with you that I feel compelled to express my displeasure. I am confident, though, that you continuously loathe this rabble, whether it lavishes you with admiration or tries to quench its thirst for excitement!

I feel compelled to express my admiration for your brilliance, determination, and honesty, and to say that I consider myself fortunate to have met you in Brussels. Anyone who isn’t one of these reptiles is glad, now more than ever, that we have individuals like you, Langevin, among us, real people with whom one feels fortunate to interact. If the rabble continues to consume your time, simply refuse to read the nonsense and leave it to the reptile for whom it was written. Warmest greetings to you, Langevin, and Perrin, from yours sincerely, Einstein, Albert.

P.S. Using a humorous witticism, I’ve deduced the statistical rule of motion of the diatomic molecule in Planck’s radiation field, naturally under the restriction that the structure’s motion obeys conventional mechanics. However, my chances of this law being legitimate in practice are slim.” On November 23, 1911, Albert Einstein said the following. Haters will continue to hate. Don’t bother with the comments. (As a side note, “Perrin” alludes to Jean Perrin, a Curies and Langevins family friend who supported Curie in the aftermath.) Astrobiologist David Grinspoon discovered this letter to Curie while browsing through the hundreds of Einstein documents just made accessible online by the Princeton University Press.