High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is a treatment that uses high-frequency sound waves to kill cancer cells. Because HIFU does not pass through solid bone or air, it is not appropriate for all cancers. This treatment is provided by a machine that emits high-frequency sound waves. These waves direct a powerful beam to a specific area of cancer. The high-intensity ultrasound beam is directed directly at cancer, heating it up and killing it.

While low-intensity ultrasound has been used as a medical imaging tool since the 1950s, experts are now using and expanding models that help capture how high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) can work on a cellular level. Researchers are getting closer to making the use of acoustic waves to target and destroy cancerous tumors a reality.

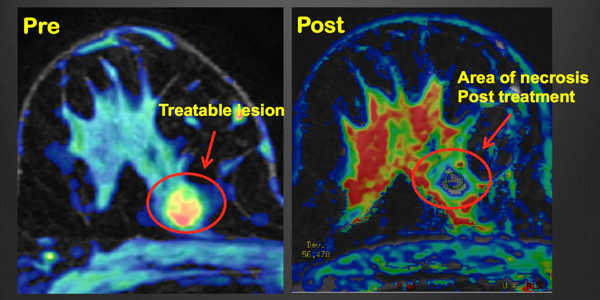

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is a prostate cancer treatment that uses highly focused ultrasound energy to target, heat, and kill cancer cells. HIFU, unlike radiation and surgery, is a non-invasive (no incisions) outpatient procedure that does not harm healthy tissue.

While doctors have used low-intensity ultrasound as a medical imaging tool since the 1950s, experts at the University of Waterloo are using and extending models that help capture how high-intensity focused ultrasound can work on a cellular level.

HIFU can only be used to treat a single tumor or a portion of a larger tumor. It cannot be used to treat more widespread tumors. This means that HIFU is not appropriate for people whose cancer has spread to more than one part of their body.

The study, led by Siv Sivaloganathan, an applied mathematician and researcher at the Fields Institute’s Centre for Math Medicine, discovered that by running mathematical models in computer simulations, fundamental problems in technology can be solved without putting actual patients at risk.

Sivaloganathan and his graduate students June Murley and Kevin Jiang, as well as postdoctoral fellow Maryam Ghasemi, develop the mathematical models that engineers and doctors use to put HIFU into practice. He stated that his colleagues in other fields are interested in the same issues, “but we’re approaching it from different angles.”

“My contribution will be to use mathematics and computer simulations to create a solid model that others can use in labs or clinical settings. And, while the models are not nearly as complex as human organs and tissue, they provide a significant head start for clinical trials.”

One of the challenges that Sivaloganathan is currently working to overcome is the fact that while HIFU targets cancers, it also poses risks to healthy tissue. When HIFU is used to destroy tumors or cancerous lesions, the hope is that healthy tissue is spared. The same is true when intense acoustic waves are focused on a tumor on the bone, where a lot of heat energy is released. Sivaloganathan and his colleagues are investigating how heat dissipates and whether it harms bone marrow.

Engineers who are developing the physical technology are collaborating with Sivaloganathan, as are medical doctors, particularly James Drake, chief surgeon at Hospital for Sick Children, who is investigating the practical application of HIFU in clinical settings.

To raise the temperature to 70-80°C, high-power ultrasound can be focused on a specific point. To generate heat, HIFU employs sonication (sound energy). Because each sonication only heats a small focal target, the interventional radiologist will use several sonications to ablate the entire affected area. Diagnostic sonography with focused ultrasound (USgFUS or USgHIFU) or magnetic resonance guidance with focused ultrasound may be used by the interventional radiologist (MRgFUS).

Sivaloganathan believes that HIFU will significantly improve cancer treatments as well as other medical procedures and treatments. HIFU is already being used in the treatment of some types of prostate cancer.

“It’s an area that I believe will take center stage in clinical medicine,” he predicted. “It does not have the drawbacks of radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Other than the effect of heat, which we are currently working on, there are no side effects. It can also be used to break up blood clots and even to administer drugs.”