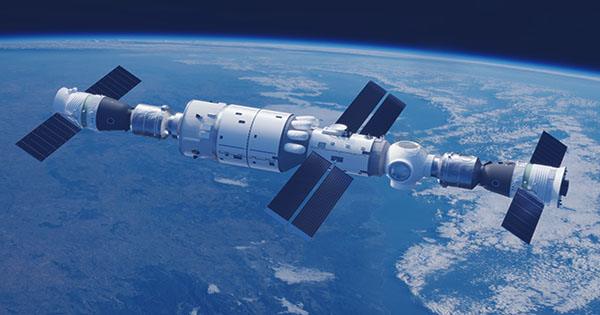

On Nov. 15, 2021, Russia used a missile launched from the surface of the Earth to destroy one of its own outdated satellites, resulting in a vast debris cloud that threatens several space assets, including personnel aboard the International Space Station.

This occurred just two weeks after the United Nations General Assembly First Committee explicitly acknowledged the critical role of space and space assets in international efforts to improve the human experience – as well as the dangers that military actions in space pose to those aspirations.

The United Nations First Committee is concerned with disarmament, global issues, and threats to world peace. It passed a resolution on Nov. 1 that establishes an open-ended working committee. The group’s objectives are to assess current and future threats to space operations, determine when behavior is irresponsible, “make recommendations on possible norms, rules, and principles of responsible behaviors,” and “contribute to the negotiation of legally binding instruments,” such as a treaty to prevent “an arms race in space.”

We are two space policy specialists with expertise in space law and the commercial space industry. We are also the president and vice president of the National Space Society, a non-profit organization dedicated to space advocacy.

It is encouraging to see the United Nations recognise the grim fact that peace in space remains precarious. This timely resolution is accepted as space operations become increasingly essential and tensions continue to escalate, as seen by the Russian test.

Outside of the Earth’s atmosphere, there is no such thing as a lawless vacuum. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which has been ratified by 111 countries, governs space activities. The pact was negotiated during the Cold War when only the Soviet Union and the United States possessed spacefaring capabilities.

While the Outer Space Treaty has broad concepts to guide governments’ actions, it lacks specific “rules of the road.” In essence, the pact guarantees all humans the right to explore and use space. There are just two exceptions to this, and several holes appear right away.

The Moon and other heavenly bodies must only utilize for peaceful purposes, according to the first caution. In this blanket restriction, it leaves out the rest of the space. The treaty’s preamble provides the sole advice in this regard, recognizing a “common interest” in the “development of the exploration and use of space for peaceful purposes.”

The second proviso states that anyone undertaking space operations must do so “while taking into account the equivalent interests of the other States Parties to the Treaty.” The lack of specific definitions for “peaceful objectives” and “due respect” in the treaty is a serious issue.

While the Outer Space Treaty expressly prohibits the deployment of nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in space, it does not restrict the use of conventional weapons or the use of ground-based missiles against space assets. Finally, it is uncertain whether some weapons, such as China’s new nuclear-capable partial-orbit hypersonic missile, should ban under the pact. The treaty’s broad military constraints give plenty of flexibility for interpretation, which might lead to confrontation.