Scientists have hired an unexpected source – the world’s brightest X-rays to be precise. An international team of scientists using X-ray beams from a European synchrotron in Grenoble, France, examined micro-flakes from the original artwork, To help better preserve the 1910 version of Stage Scream.

Combined with the non-invasive racist analysis of the paintings in their home at the Munch Museum in Oslo, the team concludes that moisture was the problem with the original preservation of the masterpiece.

The expression of concern for this painting would probably have been mirrored by the stage even today if he had known that the decay that his painters were suffering from had deteriorated.

Recalling a diary entry in 1892, Norwegian artist Edward Mancha said, “I felt a cry through nature.” The incident was the inspiration behind his infamous work, The Scream, whose sad image bears the face of someone who has just been told that in the very near future he would advise a U.S. president to inject people with antibiotics to treat the virus responsible for the global epidemic.

“Synchrotron micro-analysis has allowed us to identify the root cause of painting depletion, which is humidity,” said Letizia Monico of the National Research Council of Italy (CNR) and one of the authors of the study, published in Advances in Science. “We also found that the effect of light on the paint is slight.”

The painting was not an easy life. In 2004, two armed robbers stole 1910 artwork, along with another of Madonna’s paintings, Madonna, from the Munich Museum. Although some underworld sources have announced that the images were burned, they were finally restored two years later, with the damage described as

“Not irreparable” but the man-handling left the shape in the bottom left corner of the screen as moisture loss.

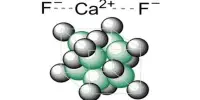

Excluding this degradation, Munch’s new “screaming color” development has proven complex in favor of preservation. In particular, the yellow cadmium-sulfide-based pigment used throughout sunset and in the neck region of the central figure has turned into an off-white color. The yellow color of the lake is also shaking.

Recent experiments with problematic cadmium pigments, starting with 1910 paintings and artificially aged mock-ups, suggest that a different image of moisture would provide more protection.

For these reasons, the painting has rarely been on display since its return about 15 years ago. Instead, it is housed in a protected storage area of the museum under controlled conditions of light, temperature about 18°C, and relative humidity (RH) of about 50 percent.

“The correct formula for permanently preserving and displaying the original version of the Scream should include the reduction of the corrosion mitigation of cadmium yellow pigment at extremely high humidity levels of the painting (trying to reach 45 percent RH), keeping light on preview standards for light painting materials.” Irina C. A. Sandu, a conservation scientist at the Mancha Museum, explained in a statement. “The results of this study provide new knowledge, which could lead to practical adjustments to the museum’s conservation strategy.”

“This kind of work shows that industry and science are interconnected and can help preserve pieces of the science industry so that the world can appreciate them for years ahead,” concluded Costanza Miliani Council (CNR) Italy, another relevant author of the national research paper.

Not only can the team’s investigations help bring Scream back into the limelight, but it could also help preserve fragments of Henry Matisse and Vincent van Gogh, whose work contains the same cadmium pigment.