The use of unused renewable energy to power NFT (Non-Fungible Token) trade aligns with sustainability goals and addresses some of the environmental concerns associated with blockchain technologies, such as the energy consumption of proof-of-work (PoW) cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin and Ethereum. Cornell Engineering researchers discovered that underutilized solar, wind, and hydroelectric power in the United States could support the exponential growth of transactions involving non-fungible tokens (NFTs).

The corresponding author of “Climate Concerns and the Future of Non-Fungible Tokens: Leveraging Environmental Benefits of the Ethereum Merge,” published July 10 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is Fengqi You, the Roxanne E. and Michael J. Zak Professor in Energy Systems Engineering at Cornell Engineering. Apoorv Lal, a graduate student in chemical and biomolecular engineering and a member of the You Research Group, is You’s co-author.

The processing of NFT transactions, which has quadrupled in the last five years, was once extremely energy-intensive but has recently become more sustainable thanks to a switch to a more energy-efficient algorithm. However, the researchers believe that the anticipated increase in annual NFT activity will more than offset those savings.

By the end of this decade, the carbon produced by NFT transactions may be roughly equivalent to that produced in one year by a 600-megawatt coal-fired power plant. NFT processing is very power-hungry, so this turns out to be a good way to take advantage of these power curtailments.

Fengqi You

Excess renewable energy, due to lack of storage capability, forces grid operators to curtail production. You’s idea would put that unused energy-production potential to good use.

“It’s the same idea as a car sitting in someone’s garage,” You explained. “If it is not being driven, it could be loaned to someone for carsharing.” In our case, underutilized wind, solar, and hydro power sources could be put to good use. Of course, this is up to industry and policymakers,” he said, “but technology-wise, we show it’s very feasible because these power sources are already available.”

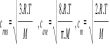

Their key discovery was that the increased NFT processing activity could be powered in part by untapped or underutilized existing power sources. Fifty megawatts of potential hydropower from existing US dams that are not currently used to generate power, or a 15% utilization of wind and solar energy that cannot currently be used or stored from Texas sources, could power an exponential increase in NFT transactions.

Blockchain technologies, including NFT transactions, provide a high level of security in a wide range of applications, but the amount of energy required to process each transaction is problematic in a warming world.

“At first, people were only concerned with the utility of these applications,” Lal explained. “But then they started to realize the energy and climate impacts, because the crux of all these applications is the utilization of massive amounts of energy.”

The authors wrote that if no efforts are made to make NFT transaction processing more sustainable, their annual emissions will be equivalent to 0.37 megatons of carbon dioxide, which is close to the CO2 emissions from 1 million single-trip flights from New York to London.

In September of 2022, the Ethereum blockchain responded to the call for more sustainable trading by switching from an energy-intensive proof of work (PoW) algorithm to a proof of stake (PoS) consensus mechanism, which requires less computing power. Energy consumption decreased drastically following the switch, known as the Ethereum Merge.

Nonetheless, the authors wrote, an increase in recorded NFT transactions would result in more validators operating on the network. By the end of this decade, the energy consumed by an exponential increase in NFT transactions could be equivalent to the energy consumed by 100,000 US households. Even if individual NFT transactions consume significantly less energy, the cumulative effect of increased numbers of validators operating on fossil fuel-dominated grids will result in an increase in the associated carbon debt.

“By the end of this decade,” you predicted, “the carbon produced by NFT transactions may be roughly equivalent to that produced in one year by a 600-megawatt coal-fired power plant.”

The authors assessed the viability of two hydroelectric energy carriers, green hydrogen and green ammonia (more energy-dense than hydrogen), noting that cost savings are influenced by a variety of factors, including transportation distances and the utilization levels of available renewable energy sources. Retrofitting these existing power sources could be difficult, according to the authors, but it would still be beneficial to energy carriers and the environment.

“NFT processing is very power-hungry,” you explained, “so this turns out to be a good way to take advantage of these power curtailments.”